It’s common for beginners and sometimes even more advanced students to lack an understanding of how Chinese characters are structured. This includes misconceptions about components and radicals. In this article, I’m going to address some of the misconceptions I have encountered as a teacher and as the “Chinese Guru” here at Skritter.

What are Chinese Radicals?

Most Chinese characters are compounds, meaning that they consist of several smaller characters. These may or may not be used as individual characters themselves, it differs from case to case. Characters are typically combined in specific ways and therefore you can’t break them down arbitrarily.

For instance, a character like 想 (xiǎng) “to think” can be broken down first into 相 and 心. Then 相 can be further broken down into 木 and 目. The three characters 心, 木 and 目 can’t be broken down further. This is the only way this character can be broken down. Thus, there is no character that combines 心 with only 木 on top.

There are four major ways of creating compounds. In this article, I’m going to explore phonetic-semantic compounds. This is the most common type of character. However, it is often the least understood by the average student. Read more about the four main types here.

Now let’s turn to radicals, which are misunderstood by a majority of students. To understand what they are and how they work, we need to look at how Chinese dictionaries are structured. Traditionally, Chinese dictionaries aren’t sorted alphabetically. Instead, they use what’s called 部首 (bùshǒu) in Chinese, meaning “section head”. For some reason, this is translated as “radical” in English.

The Purpose of Chinese Radicals

Each Chinese character has one and only one radical, which dictionaries use to sort the character into the right section. The exact number of radicals varies. In the most recent edition of 现代汉语词典, there are 201. Another standard reference for radicals is the Kangxi dictionary published in 1716 which contains 214 radicals.

Not all characters are sorted by exactly the same radical in all dictionaries, but most are. Within each section, characters are sorted by the number of additional strokes necessary to write the character. This does not include the radical.

So, a radical is a part of a character that has a special function used in dictionaries. It’s not the same as a character component, it’s not even the same thing as a semantic character component. As far as dictionaries are concerned, radicals are the part of a certain character that is used to index it, nothing more, nothing less.

This means that a certain character component, say 土 (tǔ) “earth”, can be the radical in some characters like 境 (jìng) “situation”, but not in others such as 肚 (dù) “stomach”. What kind of information do you think 土 carries in 肚?

Why all the fuss about radicals, then?

If radicals are so limited, how come everyone seems to talk about them and use them for teaching Chinese? Part of the reason is that many haven’t understood the difference between radicals and character components in general. This is evident when you hear someone say that “this character contains two radicals, 木 and 目”. No character contains two radicals, that would defy the purpose of radicals!

Character components, on the other hand, are very important to understand how characters are structured. While the radicals themselves aren’t useful unless you want to look up characters in old dictionaries. Thus, pay attention to components and what function they have.

That being said, many of the radicals also happen to be very common semantic components, so it’s sometimes convenient to use radicals as a proxy for semantic components. I did this myself when creating a list of the 100 most common radicals. You can study this list for free on Skritter:

The point isn’t that they are radicals, it’s that they also happen to be common semantic components. This is a simplification, though, and there are many common semantic components that aren’t radicals. Unfortunately, as far as I know, there is no good overview of these.

Meaning and Sound

A character component typically has one of two functions: either it carries information about sound (a phonetic component) or it carries information about meaning (a semantic component). To give you a few very basic examples, it should be obvious that in a character like 看 (kàn) “to see”, 目 is related to the meaning of the character (it means “eye”).

It should also be clear that the 马 (mǎ) “horse” in 妈 (mā) “mother” probably isn’t related to meaning. On the other hand, it’s a good guess that it is related to the sound (the pronunciation only differs in tone). The same is true for some other examples that often occur early in textbooks, such as 吗 (ma) “(question particle)” and 骂 (mà) “to scold”. These are unrelated to horses, so 马 component is included to show that the characters have pronunciation similar to 马.

Naturally, I have cherry-picked clear examples here. In some cases, it’s not obvious what function a specific component has and you need to do research into character etymology or the pronunciation of older forms of Chinese to make sure. Perhaps they sounded the same thousands of years ago, but not any longer.

Some characters are very reliable, though, check some examples here. If you want to know more about how you should use phonetic components to learn characters, read more here: Phonetic components, part 1: The key to 80% of all Chinese characters.

How to Write Chinese Radicals

Before learning new words, it is important to understand how both characters and words are created.

Note: Some radicals are characters (and even words) themselves, while others need to be combined with other components to exist outside of reference books.

There are 214 radicals used in modern Chinese. You can study the full list here. In this first section, we introduce you to 11 important and easy ones. With these 11 radicals you can begin to explore the essence of Chinese characters and word formation. This is a necessary step on the path to mastering characters.

Note: The goal is to draw user attention to the various components that make up Chinese words and aid in overall comprehension. This theory has been tested in the classroom, and now we’re trying it out on Skritter.

Character Creation

一,人,大,太,十,日,早,女,子,好

Before looking about basic character creations, I want to mention that stroke order is super important.

If you are totally unfamiliar with the idea of stroke order, check out Skritter’s free study deck: Chinese Stroke Order. This deck can help you learn most of the basic stroke order rules. You can also check out Skritter Chinese 101.

The first few characters, which are also radicals, take users through basic stroke order rules: left to right (一); horizontal strokes first (大); outside before inside (日); left vertical before enclosing (日) etc. d

This draws attention to how different radicals and components come together to form characters. Stoke order might seem difficult at first, but Skritter’s stroke level feedback will help you understand it in no time.

For example, in the character 早 (zǎo: early; morning), we see two components stacked on top of each other. Imagine the sun bursting forth from the horizon to welcome in a new day. Other characters like 好 (hǎo: good) are formed by the combination of a left and right component.

In 好 for example, try look beyond the six strokes and instead picture a woman (女: nǚ) and a child (子: zǐ) coming together to create good.

For more information, check out Arch Chinese’s article to learn more about Chinese character structures.

Word Creation

月,朋,又,友,明,朋友,口,中,文,中文

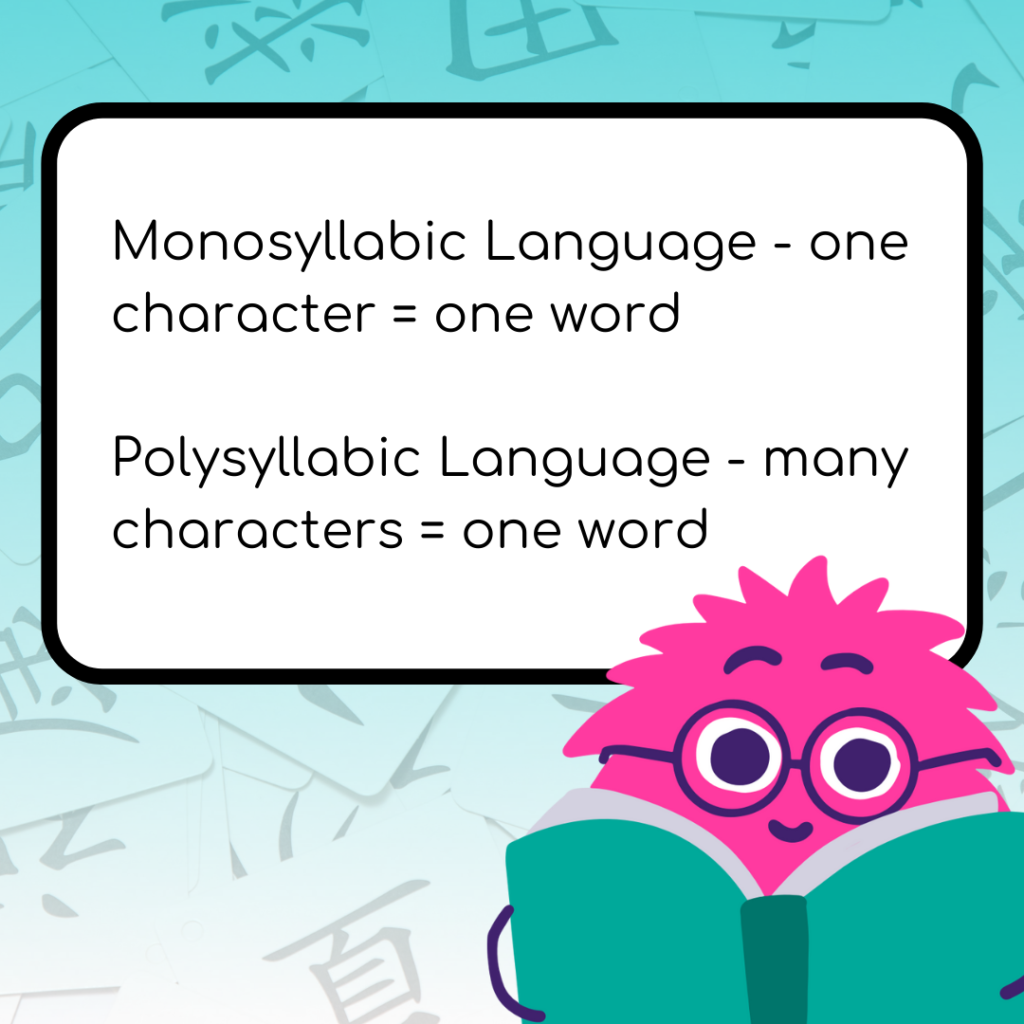

After understanding basic character creation, it is time to move onto word creation. Classical Chinese was a largely monosyllabic language. However, modern Mandarin is polysyllabic.

Words with similar meanings:

For example, this is why 朋 (péng: friend) and 友 (yǒu: friend) combined create the word 朋友 (péngyou: friend). While both characters represent the idea of “friend,” the polysyllabic word is used in modern Mandarin to convey meaning.

Let’s take another example: 海洋 (hǎiyáng: sea). Both characters represent the English for sea. However, in Modern Mandarin, they must be put together to form the word for sea. The rules for word creation are complex, but for now understand that most words consist of two (or more) characters.

Words with different concepts:

Other words, such as 中文 (zhōngwén: the Chinese language), bring two separate concepts together to create meaning. In this example, 中 (zhōng: middle) is representative of the word 中国 (Zhōngguó: China). It is combined with 文 (wén: language, literature) to create the word for Chinese.

Another such character combination is 电/電 (diàn: electricity) and 脑/腦 (nǎo: brain) which forms the word for computer 电脑/電腦. So simple and logical, right? Okay, Chinese word creation isn’t always this easy, but a lot of the words on the Chinese 101 list are to help drill this concept. When different patterns present themselves in future sections, I will be sure to discuss them.

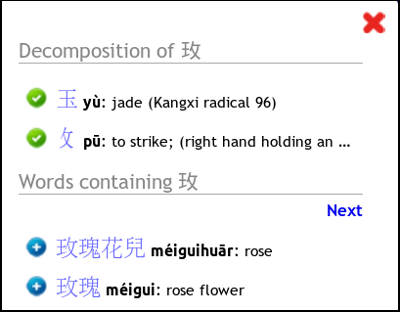

Shapeshifting Characters: Alternate Forms of Radicals

Learning some common character components is essential for effective character learning. This is why Skritter provides character breakdowns where you can see what each part means and how it’s pronounced. Both these are useful for learning characters.

However, some of them change form depending on which character we’re looking at and where in the character the component appears.

Let’s take a look at some common radicals and see how these change their form in different situations. Some of the changes are very minor and the characters would be recognisable even if written in their original form, but in other cases, the changes are so big that the alternate version(s) would be unrecognisable if you didn’t already know that they are the same character.

Slight Changes and Adjustments

Many radicals have been altered only slightly from their original form. They are typically smaller (narrower) and some strokes slope more or less than in the original character, but that’s about it. These require no actual studying, but if you care about writing correctly and clearly, you should remember even these small modifications. Let’s look at a few common ones (I have written traditional variants in brackets):

- 牛 (cow) >> 牜, e.g. 特 (special)

- 足 (foot) >> ⻊, e.g. 跑 (run)

- 羊 (sheep) >> ⺷, e.g. 羡 (envy)

As you can see, the changes are very minor indeed. 牛 has been compressed a bit and the bottom horizontal stroke has been tilted, but that’s it. The other characters have been changed to a similar extent.

Major Changes and Confusing Cases

Some characters significantly change, so, if you don’t pay attention, you might think they are different characters. There are some cases which are even more confusing because it actually looks like a different character!

Here are some common characters that undergo major or confusing changes:

- 水 (water) is perhaps the first case students learn and it’s often written as three drops of water 氵 and is used in liquids like 酒 (alcohol) and things related to liquids such as being thirsty 渴.

- 心 (heart) has at least two alternate forms. The first 忄 is so common that you probably know it well after just a few weeks of studying. The second ⺗ is confusingly similar to 小, but note that it has an extra dot, giving it the same number of strokes as the original character.

- 火 (fire) has one alternate form 灬, which makes me think of something being put on a fire so that the flames are no longer roaring. It can help quite a bit thinking of this as fire rather than just four dots.

- 犬 (dog) is common in some animal names or words related to animals, and is written 犭, again very different from the original character. This is part of the character 狗 (dog), but note that 犬 can also be used to mean “dog”, but is more formal (read more here).

- 玉 (jade) is perhaps the most confusing radical of all, because as a radical it looks like 王 (king). Therefore, the radical that is written ⺩ does not mean “king” but is in fact 玉 (jade). It’s fairly common for Skritter users to ask about this, because you’d expect something like 玫瑰 (rose) to contain 王 (king), but this isn’t the case.

Conclusion:

As you can see, these cases require special attention, otherwise you might end up thinking that the character breakdown is incorrect or that a single character in two forms is actually two different characters. Of course, from a practical point of view, you still have to learn how to write both, but you should know that they are the same character.

Study Chinese Radicals on Skritter

Interested in learning more about the Chinese radicals? Here are some great study decks to try:

Now that you’ve learned more about radicals, check out How to Write Chinese Characters: The Beginner’s Guide.