In this week’s blog post, we’ll be wrapping up our posts on tone sandhi with the infamous third tone. For those of you who’ve missed the previous posts, check them out in the links below.

- Tone Sandhi: Tone Changes for the Character “一”

- Tone Sandhi: Tone Changes for the Character “不”

- The Neutral Tone Deymistified

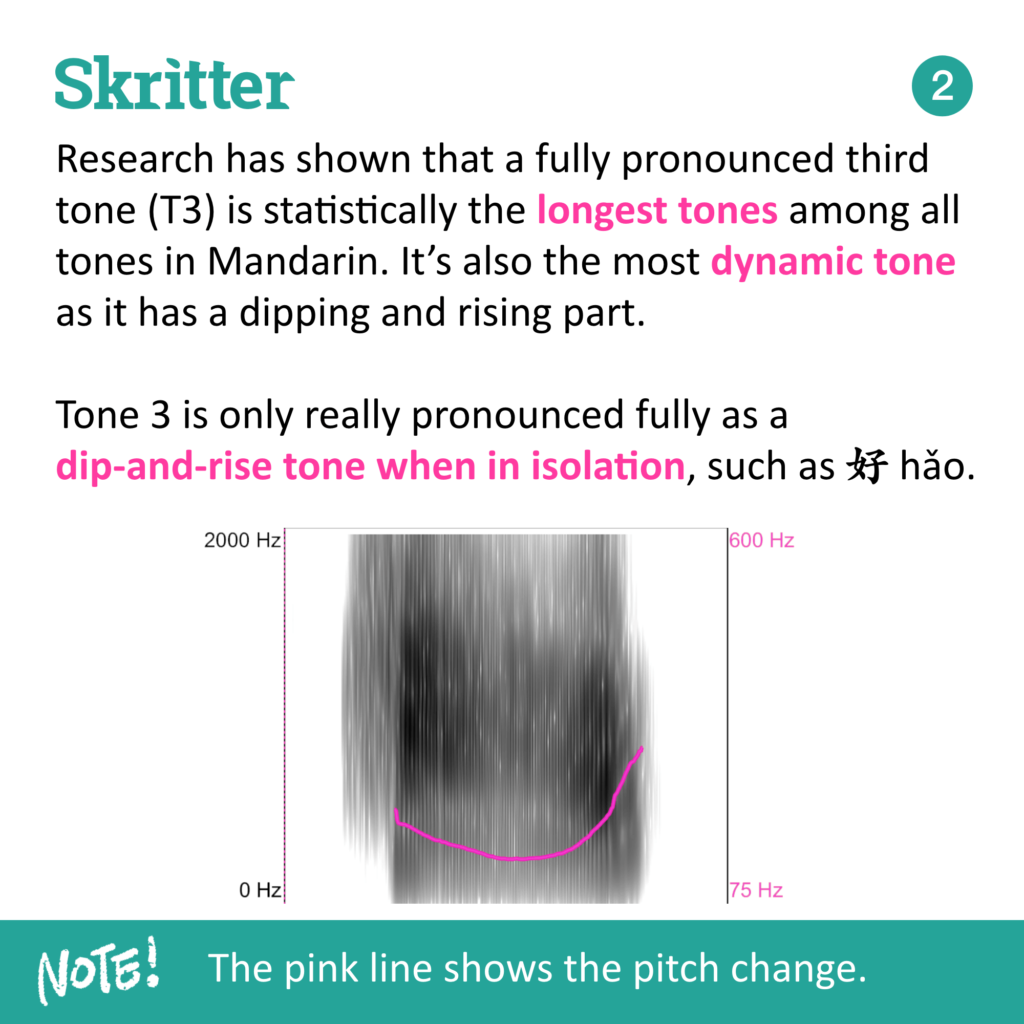

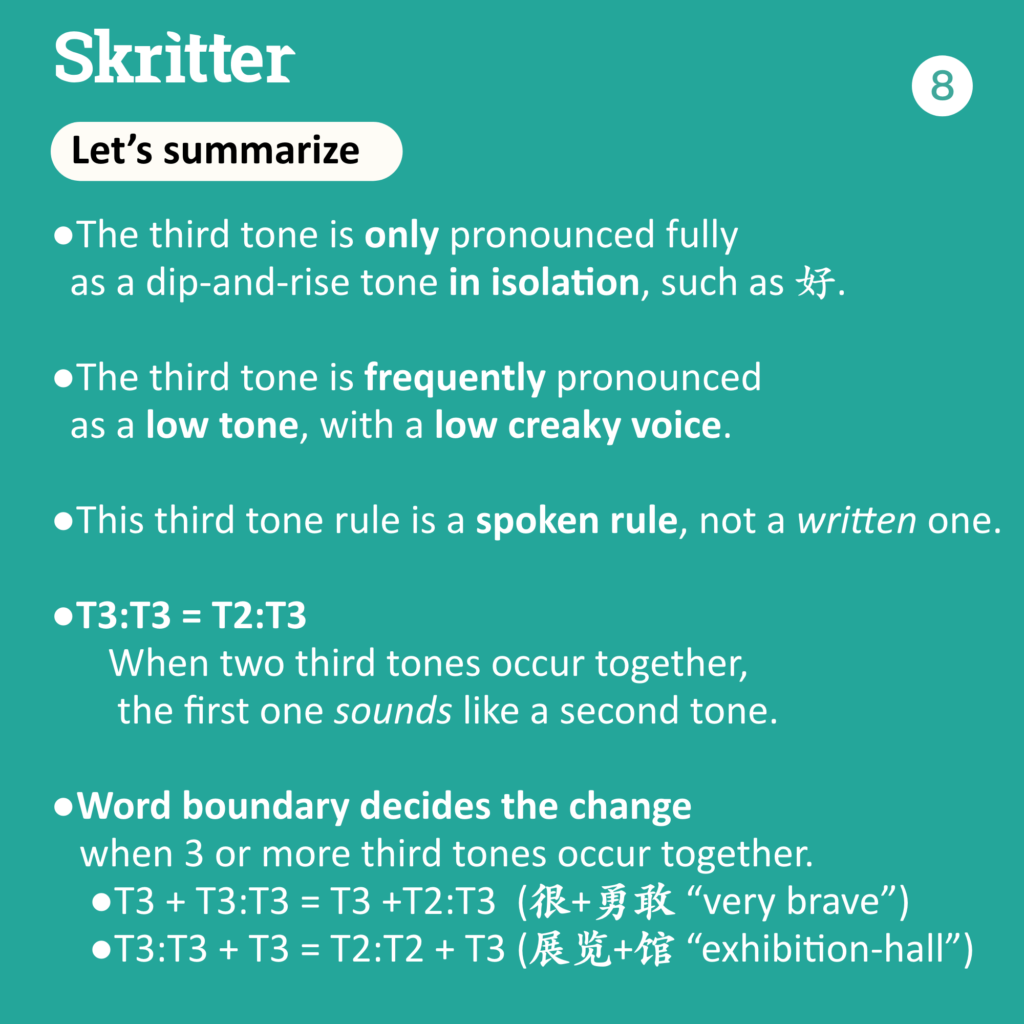

The third tone, known as both 第三聲/第三声 (dìsānshēng) or 上聲/上声 (shǎngshēng) respectively, causes a lot of problems for second language learners. The main problem is that it has two inherently different pronunciations as shown here in an image borrowed from Olle’s great blog, Hacking Chinese.

|

| Falling and rising tone vs. the low falling tone |

The Standard Third Tone

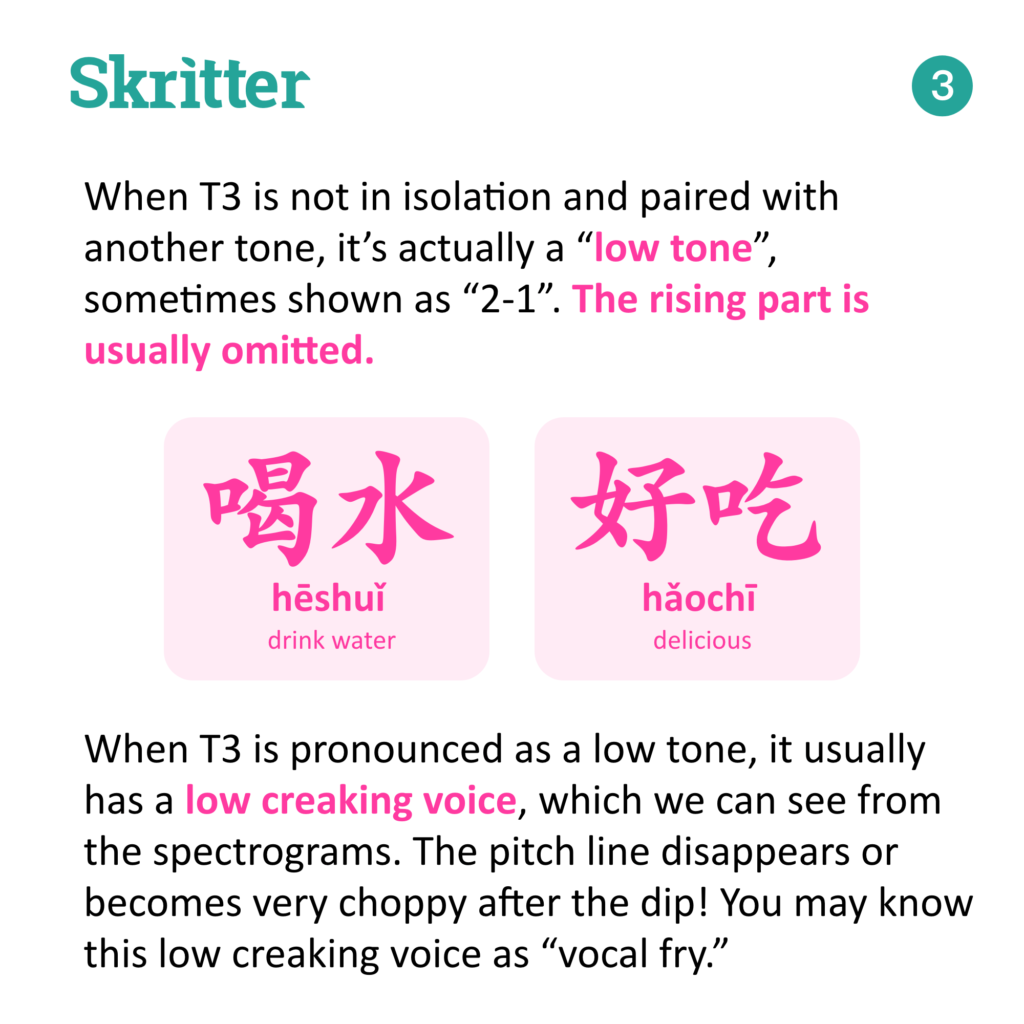

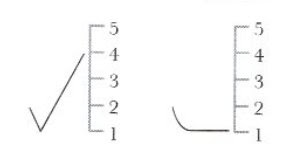

As the image above suggests, the third tone can exist as either a falling and rising tone (often represented as 214), or as a low-falling tone (represented as 21). The standard third tone only exists when a character exists in isolation, or when appearing at the end of a phrase or sentence. To better understand this concept, let’s take a look at a few examples below:

- 好 (hǎo)

- 開始/开始 (kāishǐ)

- 我們一起走/我们一起走 (wǒmen yìqǐ zǒu)

For the examples above the final third tones should be pronounced using the standard 214 falling rising pattern.

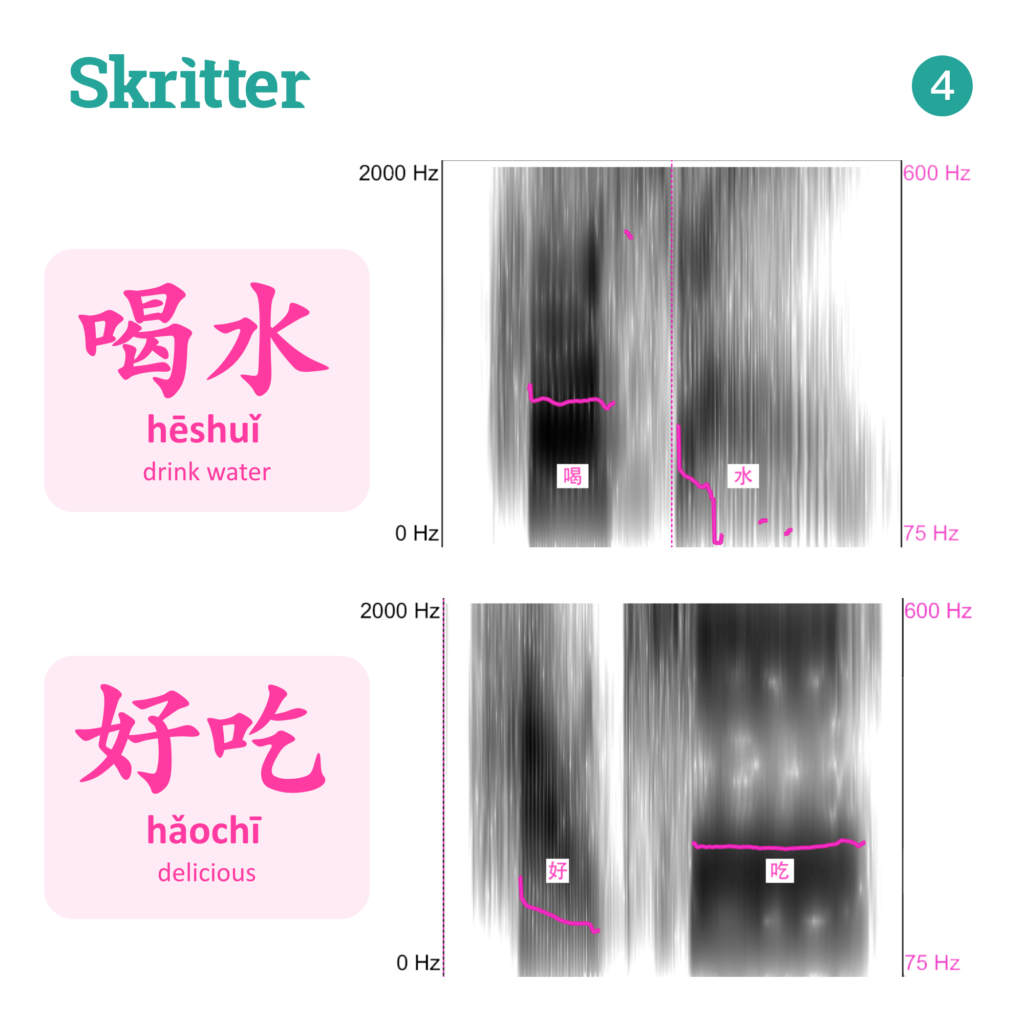

1.The Low-Falling Tone

The most common pronunciation of the third is actually as a low-falling tone. This low-falling tone occurs when a third tone appears before any first tone, second tone, or fourth tone characters. Students should make note of this both when speaking Chinese, and also listening to natives speaking Chinese, as the third tone will not sound like the standard third tone we learn when first practicing our mā, má, mǎ, mà. Now let’s take a look at a few examples:

- 老師/ 老师 (lǎoshī)

- 火車/ 火车 (huǒchē)

- 緊張/ 紧张 (jǐnzhāng)

- 語言/ 语言 (yǔyán)

- 以前 (yǐqián)

- 可能 (kěnéng)

- 討論/ 讨论 (tǎolùn)

- 馬上/ 马上 (mǎshàng)

- 土地 (tǔdì)

As you’ve probably noticed with the above examples, the third tone mark remains the same as the standard isolated third tone pronunciation, which means we have to internalize the tone change and work on applying it to spoken Chinese.

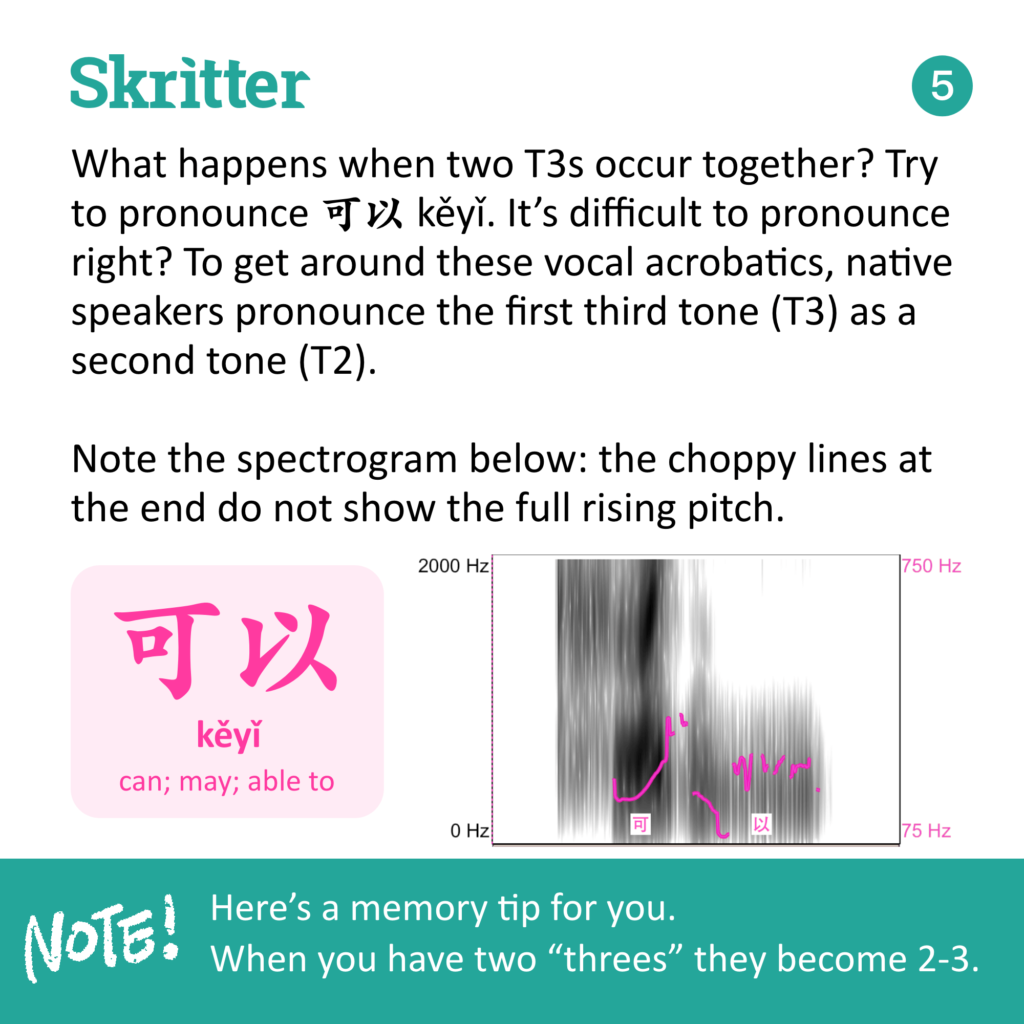

2. Two Third Tones in a Row

The most commonly known tone sandhi change takes place when two third tones appear together in a word or phrase. In this instance, the first character becomes a rising tone (or second tone) while the second character remains a standard third tone. If the word appears in the middle of the sentence, however, the second character is generally pronounced as the low-falling tone, rather than a full third tone. This change should occur rather naturally so that the speaker can maintain a standard level of fluency while communicating. Now let’s take a look at a few examples:

- 處理/ 处理 (chǔlǐ)

- 理解 (lǐjiě)

- 所以 (suǒyǐ)

- 老闆/ 老板 (lǎobǎn)

- 影響/ 影响 (yǐngxiǎng)

- 管理 (guǎnlǐ)

Here’s an example of third tone words in a sentence. If you read them out loud you should notice just how much more fluid the sentences sound when using low-falling tones rather than a full third tone.

(T) 有空的時候,請給我打電話

(S) 有空的时候,请给我打电话

(P) Yǒu kòng deshíhòu, qǐng gěi wǒ dǎdiàn huà.

(T)由於老闆非常了解他的想法,所以才準許了他的請求

(S)由于老板非常了解他的想法,所以才准许了他的请求

(P) Yóuyú lǎobǎn fēicháng liǎojiě tā de xiǎngfǎ, suǒ yǐ cái zhŭnxŭ le tā de qǐngqiú.

(S)由于老板非常了解他的想法,所以才准许了他的请求

(P) Yóuyú lǎobǎn fēicháng liǎojiě tā de xiǎngfǎ, suǒ yǐ cái zhŭnxŭ le tā de qǐngqiú.

Similar to the low-falling tone examples, you’ll notice that the pinyin for the first third tone character doesn’t change to a second tone. Again, students need to simply internalize the tone changes and apply them naturally when reading aloud or communicating.

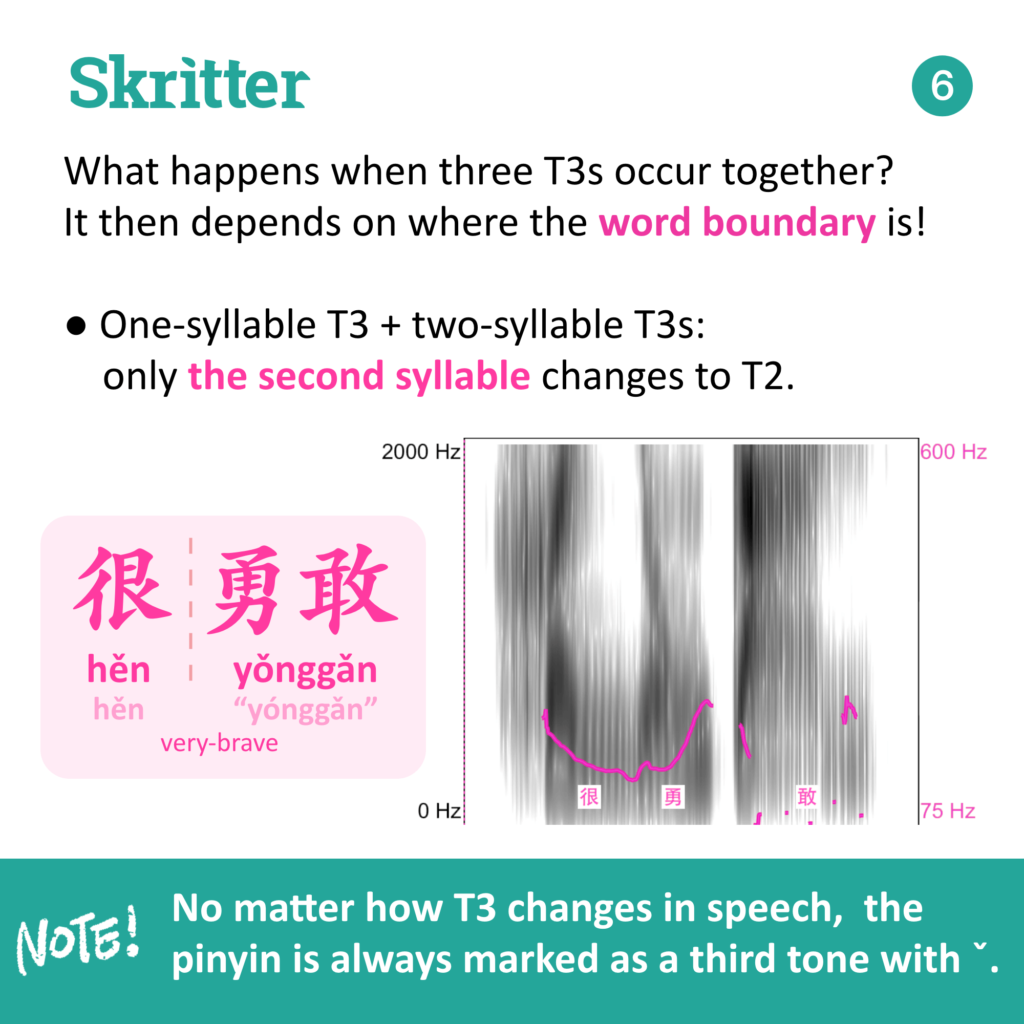

3. Three or More Third Tones

When three or more third characters appear together, things start to get a little muddled. This is because the tones changes depend of whether or not the three characters are a word or a phrase, and order between the dissyllable (雙音節/双音节: shūangyīnjié) and the monosyllable (單音節/双音节: dānyīnjié). When a dissyllable appears before the monosyllable the first two characters should be read as a rising tone (second tone), like in the examples found below:

- 演講稿/ 演讲稿 (yǎnjiǎnggǎo)

- 蒙古語/ 蒙古语 (měnggǔyǔ)

- 展覽館/ 展览馆 (zhǎnlǎnguǎn)

- 洗臉水/ 洗脸水 (xǐliǎnshuǐ)

When the monosyllable appears before the dissyllable, however, the first character should be read as a falling-low tone, while the second character is read as a rising tone (second tone) and the third character is read as a full third tone. Oftentimes, a slight pause is added between the first and second characters for emphasis and clarity of meaning. Now let’s take a look at some examples:

- 買保險/ 买保险 (mǎi bǎoxiǎn)

- 紙老虎/ 纸老虎 (zhǐ lǎohǔ)

- 很勇敢/ 很勇敢 (hěn yǒnggǎn)

- 有理想/ 有理想 (yǒu lǐxiǎng)

As you can tell from the above, these tone sandhi rules are a little more complicated than the ones for “一” and “不”. I hope, however, that you’ve learned a lot with this post, and that you’ll start to notice the various tone changes while listening to Chinese. Hopefully, after time these third tone rules will become internalized into your own understanding and production of the language!