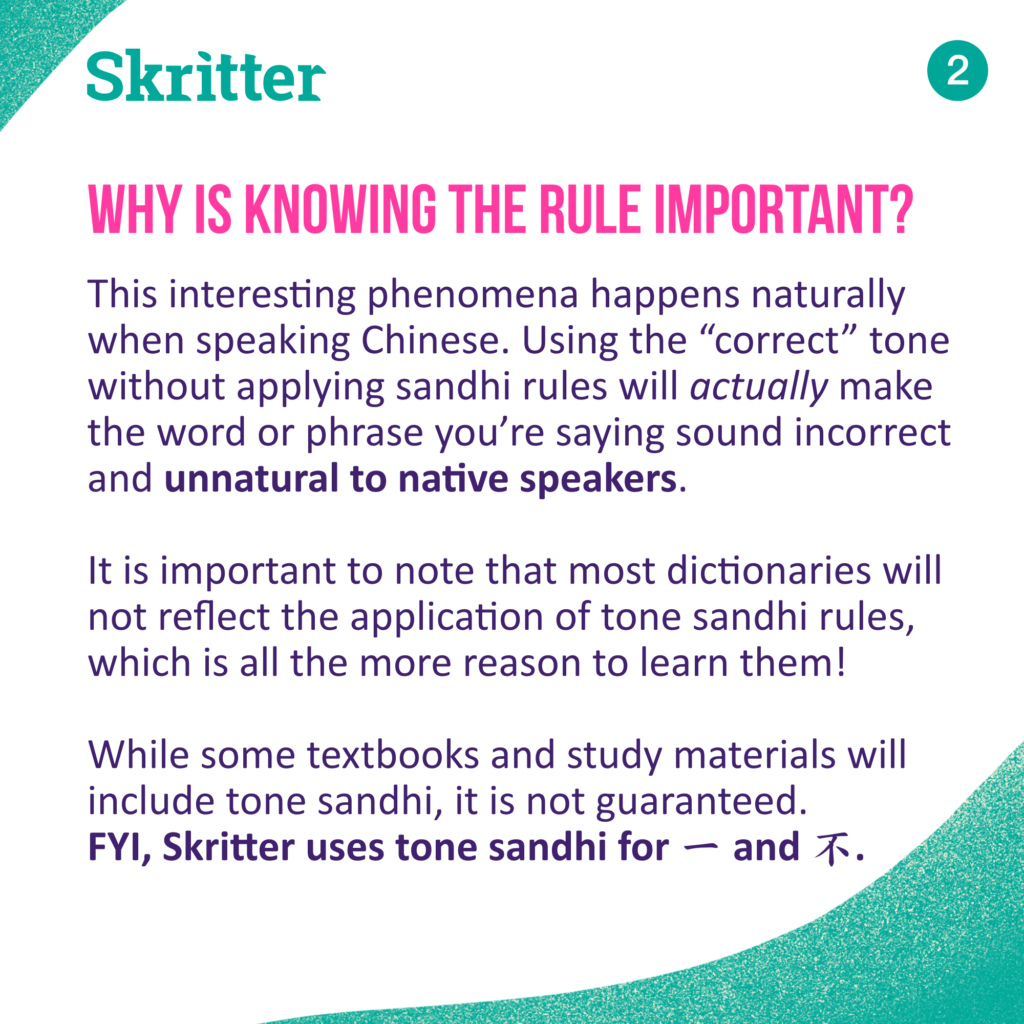

Studying words on Skritter I’m sure you’ve noticed when “不要” (don’t want) gets written as “bú yào” rather than “bù yào,” or “一般” (general; ordinary) becomes “yì bān,” rather than “yī bān.” This isn’t some glitch in the matrix, or a mistake that needs reporting–in fact, what you see is an interesting phenomena that exits in Chinese called tone sandhi. According to “Mandarin Chinese: A Function Reference Grammar” tone sandhi can be described as:

“a syllable that has one of the tones in the language when it stands alone, but the same syllable may take on a different tone without a change in meaning with it is followed by another syllable.”

While the concept of tone sandhi is usually first brought up in beginner lessons (think “你好”), the overall rules are generally ignored by most dictionaries and teachers, forcing students to sink or swim when it comes to actually producing them in every day speech. Today’s post tackles the first of the three most common examples of tone sandhi in Mandarin Chinese, which are:

- Tone changes for the character “一” (yī: one)

- Tone changes for the character “不” (bù: not; no)

- Tone changes for 上聲/上声 (shǎng shēng: third tone) characters

Tone Change Rules for “一”

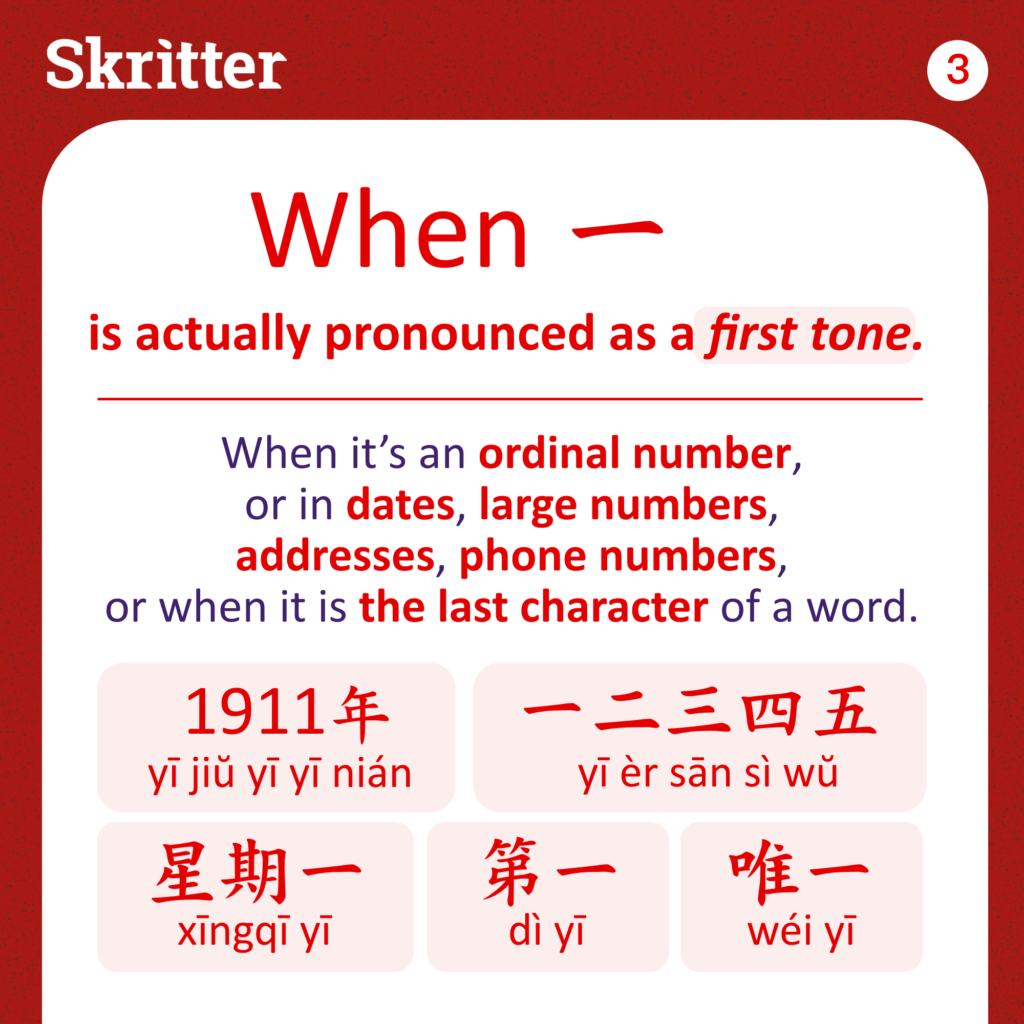

The character “一” rules are tricky, because there just so many! When learning to count in Mandarin the character seems easy enough: a simple first tone. However, it is actually only pronounced as a first tone when serving as a ordinal number, or when it is the last character of a word, for example:

When “一” is a pronounced as a first tone.

- 1911年 (yī jiŭ yī yī nián)

- 一二三四五 (yī èr sān sì wŭ)

- 第一 (dì yī)

- 星期一 (xīngqī yī)

- 唯一 (wéi yī)

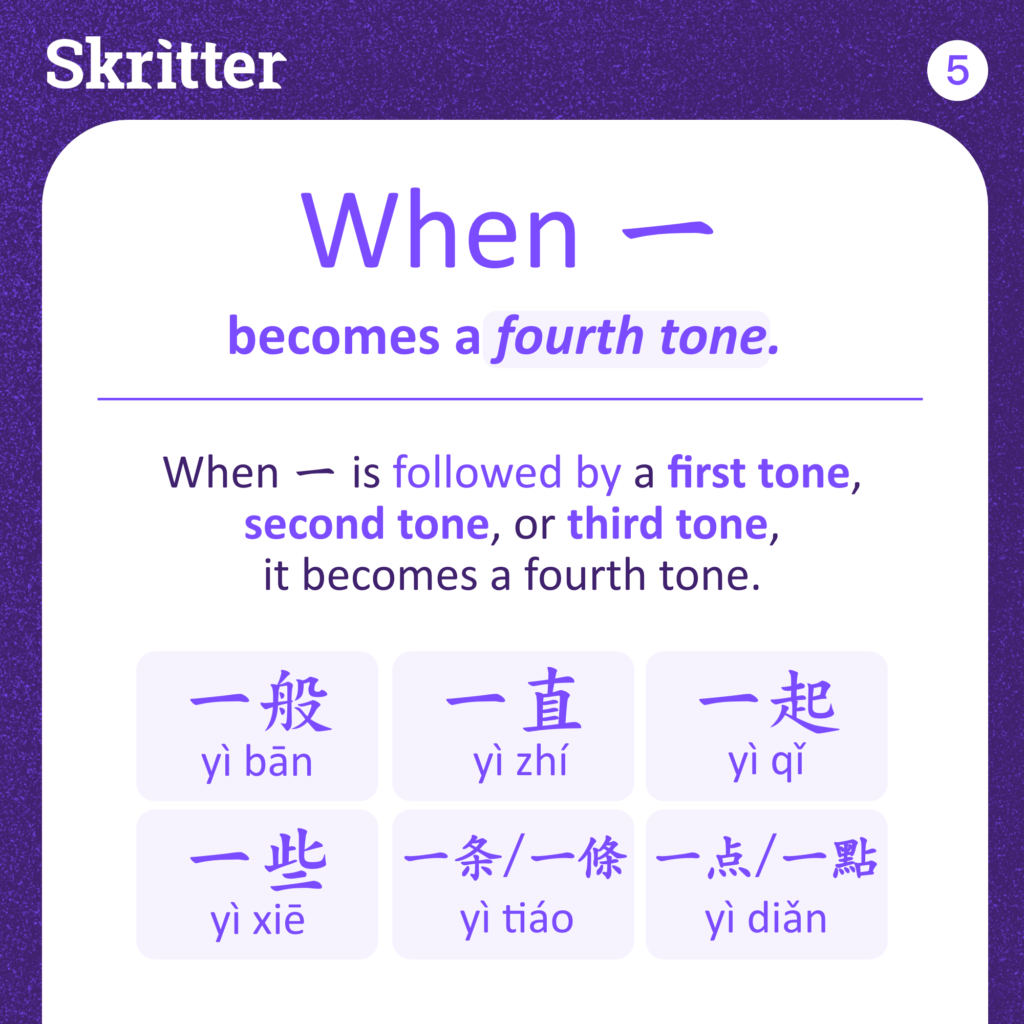

1. “一” Becomes a Fourth Tone

However, when the character “一” is followed by a first tone, second tone, or third tone, it becomes a fourth tone.

For example:

- 一般 (yì bān)

- 一些 (yì xiē)

- 一直 (yì zhí)

- 一條 (yì tiáo)

- 一起 (yì qǐ)

- 一點 (yì diǎn)

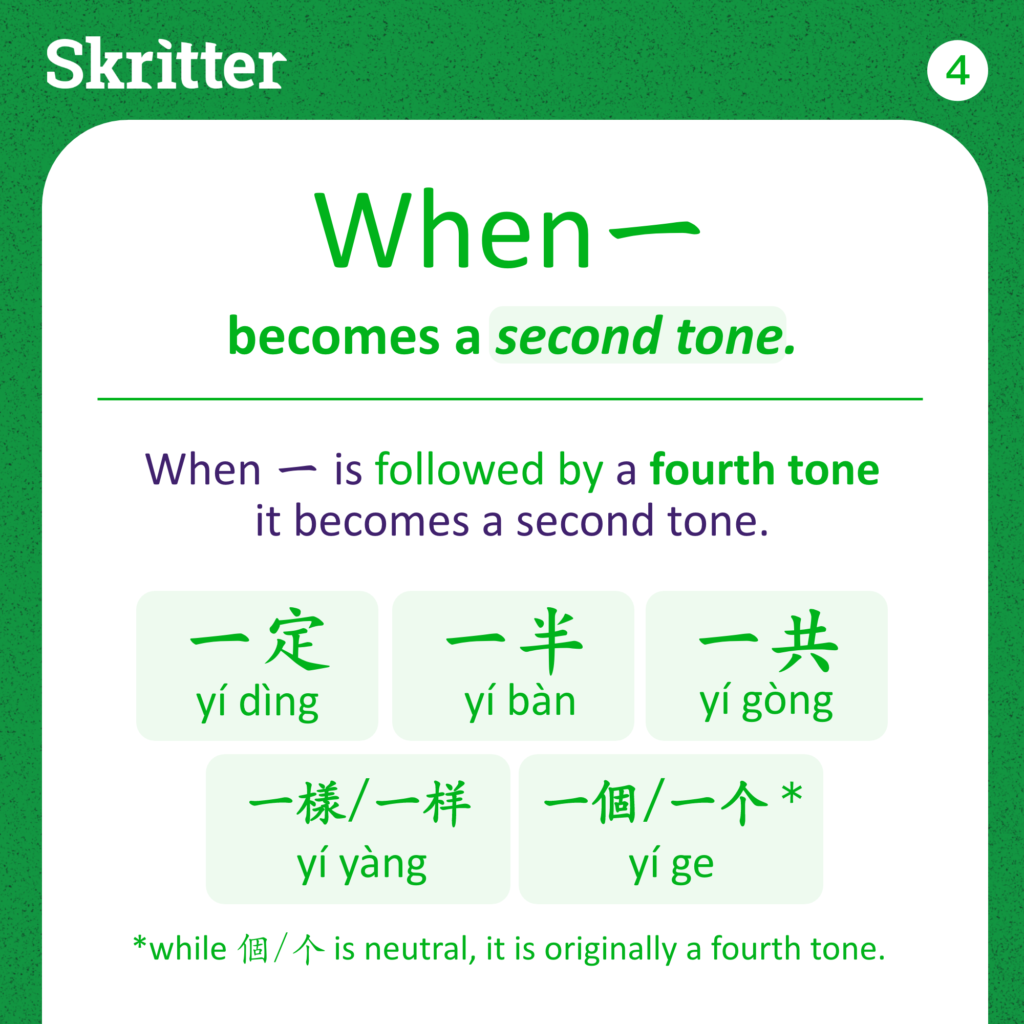

2. “一” Becomes a Second Tone

When the character “一” is followed by a fourth tone, it becomes a second tone. For example:

- 一定 (yí dìng)

- 一樣/一样 (yí yàng)

- 一半 (yí bàn)

- 一個/一个 (yí ge) *while “個/个” it is originally a fourth tone.

- 一共 (yí gòng)

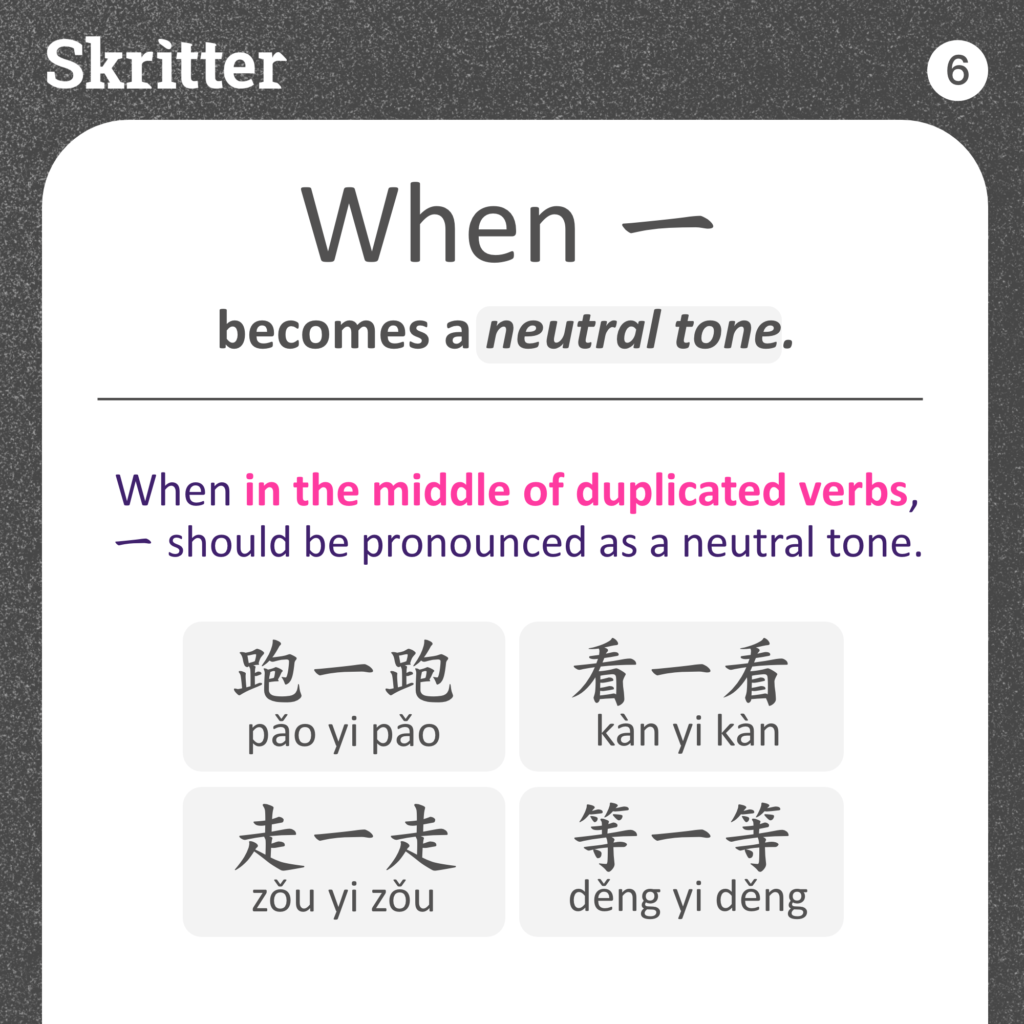

3. “一” Becomes a Neutral Tone

It doesn’t stop there. The last tone change rule involves verb reduplication. When in the middle of duplicated verbs, “一” should be pronounced as a neutral tone. For example:

- 聽一聽/听一听 (tīng yi tīng)

- 看一看 (kàn yi kàn)

- 走一走 (zǒu yi zǒu)

- 等一等 (děng yi děng)

Did you learn these tone changes when you started studying Chinese? Can you apply them at will? Hopefully, after today’s post, you’ll have a better understanding of what the heck is really going on with the character “一.”