This is the last and final post about confusingly similar Chinese characters. In the first article, there was a quiz where you could check how many of these characters you know, so if you haven’t taken the quiz yet, I suggest you do that before you continue reading this post.

Last week, I explained the answers to the first half of the confusingly similar character pairs and triplets, this week it’s time for the remaining seven characters.

土 (tǔ) “earth, soil”, 士 (shì) “warrior, scholar”

As was the case with 未 and 末, the only difference between these two characters is the length of the horizontal strokes. The first character, 土 (tǔ) “earth, soil”, has a short stroke on top and a longer stroke at the bottom. It’s a common character (624th), both used on its own and in compounds such as 土地 (tǔdì) “land, territory” and 土豆 (tǔdòu) “(Mainland) potato, (Taiwan) peanut”. It’s also one of the five elements.

The second character is 士 (shì) “warrior, scholar” and has the opposite strokes, i.e. a long one at the top and a short one at the bottom. This character is also common (368th) and means “warrior“ in some common words, such as 士兵 (shìbīng) “soldier”, but is more related to studying in other words, such as 博士 (bóshì) “doctor, Ph.D.”.

Since these characters mean completely different things, there are no real communication issues if you get them wrong (the reader will be able to guess what you meant), but if you want to write correct characters, do pay attention to the length of the strokes. This of course includes when these characters are found as component parts in other characters!

夭 (yāo) “young”, 天 (tiān) “sky”

This example is similar to 千 and 干 in that the difference is the slope and direction of the first stroke. In 夭 (yāo) “young”, the first stroke should be written from right to left and slope gently down, whereas in 天 (tiān) “sky” the first stroke is a normal horizontal stroke from left to right.

夭 (yāo) “young” is not a common character in itself, but it is contained in some common characters, such as 笑 (xiào) “laugh, smile”. Thus, if you write the bottom part of that character like you write 天 (tiān) “sky”, you’re not doing it right.

天 (tiān) “sky” is of course a very common character (55th) and appears early in many textbooks. It can also mean “day” and is most commonly seen in words like 今天 (jīntiān) “today”, 明天 (míngtiān) “tomorrow”, and 昨天 (zuótiān) “yesterday”.

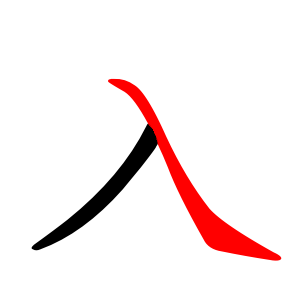

入 (rù) “enter”, 八 (bā) “eight”, 人 (rén) “person”

The last group of confusingly similar characters is perhaps the most confusing one. All three characters are common both as individual characters and as character components, making it hard to remember which one is which. Knowing their basic form and meaning makes it a lot easier to remember which of them should go in a specific compound! Rather than trying to remember the details of the strokes, it’s better to remember the meaning of that component.

入 (rù) “enter” is the 193rd most common character and is written first with a down-left stroke and then the down-right stroke, obviously longer and leaning over the first stroke. It also has a slight hook at the beginning. This character is most commonly seen in words like 加入 (jiārù) “to join” and 进入 (jìnrù) “to enter”.

八 (bā) “eight” should be familiar to anyone who has studied for more than a few weeks and is the 282nd most common character. It is written with the same stroke order as 入 (rù) “enter”, so the only difference is that the two strokes shouldn’t touch each other. Also, the second stroke doesn’t have the characteristic hook that makes 入 easy to recognize. Sometimes, “eight” is also written with more vertical strokes of almost equal height There is also a fraud-proof version of 八 which is harder to confuse (and change): 捌.

Finally, 人 (rén) “person” is also a very common character (6th) and it’s usually one of the first characters students learn. Note the difference between this and the other two characters, though! 人 (rén) “person” is written with the same stroke order as the others, but the first stroke should be longer and leaning over the second stroke that supports it. In a way, it’s the opposite of 入. Apart from being a very common character in words, 人 is also common as a character component, but pay attention, because it might change shape!

What characters do you find confusingly similar?

I have now covered seven groups of confusingly similar characters and I hope this will help you write better characters and confuse similar ones less. There are more similar characters out there, though. Do you have a set of two, three, or even four characters that you find annoyingly similar? Leave a comment and share!