Last time, I wrote a post about how small changes could make a big difference in the meaning of some Chinese characters. I also wrote about how difficult it is as a beginner to figure out exactly which stroke lengths, placements and angles are crucial for determining the meaning and not just if the character looks good or not.

In that article, I also included a quiz with fourteen characters that are easy to confuse with one or two other characters that differ only slightly. Here are the characters I used, but I encourage you to go to the previous article and do the quiz before you continue reading this one!

己/已/巳, 未/末, 千/干

土/士, 夭/天, 入/八人

Below, I’m going to explain the differences between the characters in the first three groups, the rest will be covered in a similar article next week:

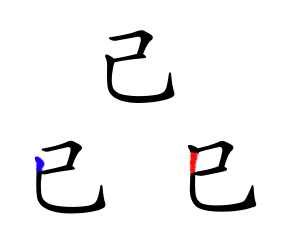

己 (jǐ) “self”, 已 (yǐ) “already”, 巳 (sì) “the sixth heavenly branch”

The difference between these three characters is where the third stroke starts

In the first case, 己 (jǐ) “self”, it shouldn’t go beyond the horizontal second stroke (it still does sometimes, but it’s just the beginning of the stroke that protrudes above the second stroke). 己 is a common character (131st) and appears most commonly in the word 自己 (zìjǐ) “self, oneself”. This character is also common as a component in other characters, such as 记 (jì) “register, record”.

In the second case, 已 (yǐ) “already”, the third stroke clearly starts above the end of the second stroke, but it doesn’t touch the first stroke. This is also a very common character (95th) and most commonly appears in the word 已经 (yǐjīng) “already”. Think of it as the stroke as “already” gone past the horizontal stroke.

In the third case, 巳 (sì) “the sixth heavenly branch”, the third stroke goes all the way up and joins with the first stroke. This character is not so common on its own (it’s not even among the most common 3000 characters). However, it is common as a component in other characters, such as 包 (bāo) “wrap”.

末 (mò) “tip, end”, 未 (wèi) “not yet, have not”

Both these characters are based on the character 木, which is a pictograph of a tree. By adding a vertical line marking the top of the tree, the writer could represent the tip or end of the tree (or of something else by extension). This character is fairly common (1272nd) and is taught in most beginner courses in the word 周末 (zhōumò) “weekend”, i.e. the end of the week.

The second character, 未 (wèi), is much more common (399th), especially in written Chinese. It means “not yet” or “have not” and the first example students learn is typically 未来 (wèilái) “future”, i.e. something that has not yet arrived. This character is very common as a negation in written Chinese and there are many, many uses of it, but here are two examples: 未知 (wèizhī) “unknown”, 未必 (wèibì) “not necessarily”.

The only difference between the two characters is the length of the horizontal strokes. I remember these two by thinking of the origin of 末; the longest stroke marks the important part (i.e. the tip of the tree).

千 (qiān, thousand), 干 (gān/gàn)

These two characters are very similar and can be easy to confuse, especially when reading. Writing is not so bad, because they are written with different strokes.

The first character, 千, is written with the first stroke sloping down and left, whereas the second character 干 has a normal, horizontal, left-right stroke. This is a good example of when stroke order matters! If you use handwriting input, you’re much more likely to get the right character if you get the stroke direction right. In other words, the characters are visually similar but written differently.

千 (qiān), “thousand” is a common character (410th) and usually appears in numbers. There is also a fraud-proof variant of this character, which has an added person radical: 仟.

干 is more complicated because it’s the simplification of several different traditional characters (four, actually, 乾, 幹, 干, 榦, but the last two aren’t very common).

- 乾 “gān” means “dry” and is first encountered in the word 乾淨/干净 (gānjìng) “clean”.

- 幹 “gàn” means “do” (and also means the f-word) and is most commonly heard in phrases like 幹嘛/干嘛 (gànma), meaning “what are you doing”.

Thus, in simplified Chinese, the character 干 has several completely different usages with different pronunciations! The confusion between 干 and 千 seldom occurs in traditional Chinese because 干 isn’t very common.

—

The remaining three groups will be the subject of a similar article next time. By way of rounding this one off, though, I’d like to address a key question. Does it matter? If you write 己经, 周未 or 两干块, most people will understand what you mean, they might not even notice the incorrect characters if they don’t pay attention. So why bother?

There are several reasons. First, some of the differences are crucial when dealing with handwriting input. If the strokes are in different directions, such as for 千 and 干, the input method won’t recognize the character if you get it wrong (for instance, you can’t write these characters using Google’s handwriting recognition with the wrong stroke direction).

Second, writing things correctly gives a neat and thorough impression. You can certainly understand what I want to say in English if I write “They have recieved teh pakcage”, but I think most of us share the idea that following a common standard is good and generally improves communication.

That said, the only place someone is going to really care about what you write is probably in a classroom or when you sit for an exam. This doesn’t mean that it’s unimportant, but it means that you need to decide for yourself how thorough you want to be!