In a recent article, we discussed a cornerstone of successful vocabulary learning, namely the spacing effect:

The spacing effect is one of the most important things underpinning how Skritter works. By spreading review over time, learning becomes much more efficient. But the spacing effect is not limited to vocabulary learning, it can be applied to other areas too! Read more…

In this article, we will look at another of these cornerstones which is at least as important: the difference between active recall and passive reviewing.

Active recall for successful, long-term learning

Put very briefly, active recall simply means that if you want to remember something, actively searching for the correct answer in your memory is much more efficient than simply seeing the answer one more time.

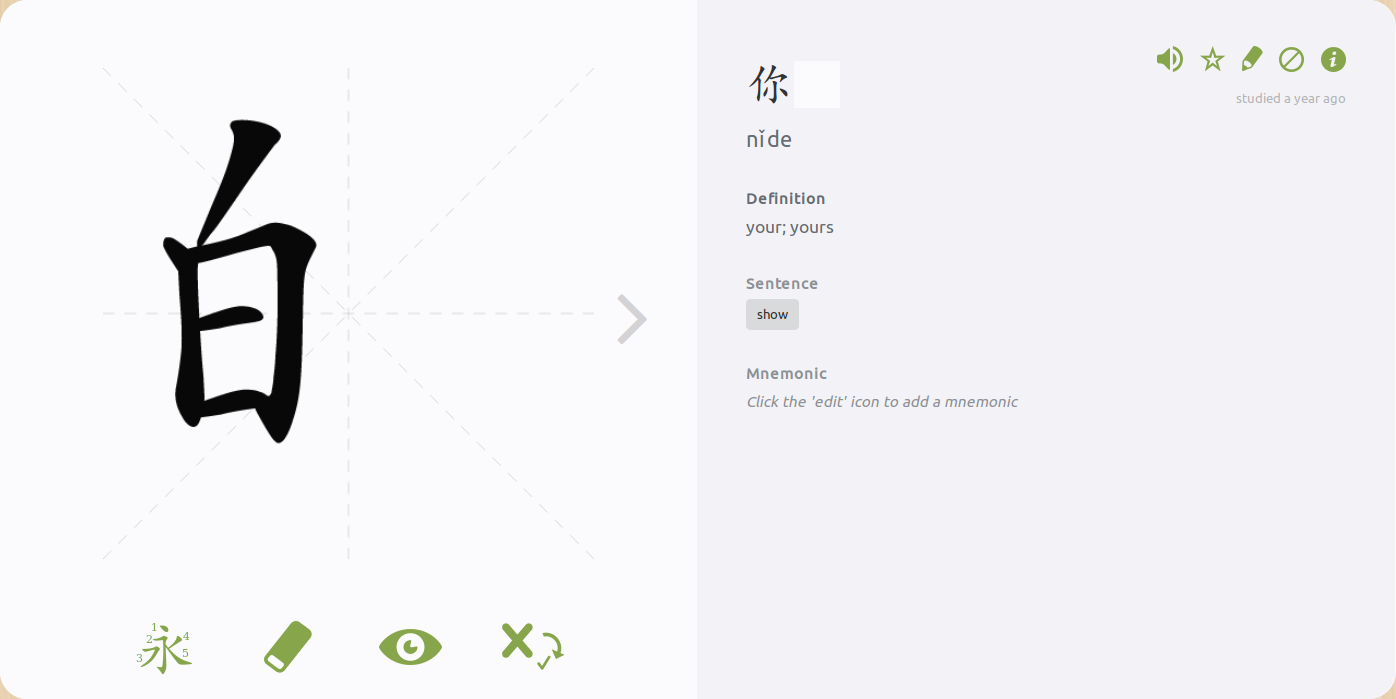

For example, if you want to remember that 记得 means “to remember” in Chinese, it’s much more efficient to try to answer the question “What does 记得 mean?” than seeing that it means “to remember” directly. The is one of the reasons flashcards are so useful for studying in general.

Exposure is good, but it’s often not enough

Naturally, this means that the answer to each prompt in Skritter is what you practice the most. Mere exposure is also helpful, but not to the same extent.

For example, if you have a tone recall prompt in Skritter and you’re asked to give the tones of 记得, you will also reinforce your memory of what the characters look like and what they mean, even if that information is displayed.

However, the effect is much weaker than that for which the prompt has been designed (tones in this case). To really learn to write characters, you have to have writing prompts. You will learn to write some characters just by reading them, but in most cases this will not be enough.

Active recall and deep processing

This is also true when you study characters and words in general and is the main reason I advise students against copying new characters stroke by stroke. If you’re looking at the target character or word when writing it, you’re not doing active recall. You’re not processing the character deeply enough.

In essence, you’re not even trying to remember how to write the character. Think of it as a sketchpad which erases itself if you don’t actively think about what’s drawn on it*: if you copy stroke by stroke, the information goes to the working memory and is immediately used to produce the right result on the paper. Long term memory is not involved. This is a clearly not a good idea.

* I didn’t choose this metaphor arbitrarily. In the most influential model of how the working memory functions (Baddeley and Hitch, 1974), there is indeed a system called the visuo-spatial sketchpad.

By creating flashcards that ask you to retrieve the right information, you make sure that you have the ability to do so when needed. The deeper processing leads to more lasting connections in your long-term memory.

Naturally, context matters too, so recalling how to write a word at home is not the same as coming up with it quickly in an oral exam and so on, but the basic principle is still sound.

Two kinds of active and passive

Note that I’m not saying that “passive” skills such as reading and listing aren’t as important or good as “active” skills like writing and speaking. You can have active recall for passive skills, such as being prompted to give the meaning of a spoken or written word instead of just hearing or seeing it along with the meaning.

Conclusion

That it’s a good idea to test yourself actively through flashcards or otherwise has been shown many times. If you’re interested in reading more, you can start here (Wikipedia), but for the rest of you, rest assured that Skritter is based on solid research into how we learn to remember things!