If you’re studying Japanese, you’re probably already familiar with the concept of yakuwarigo (役割語), however you might not have known it’s name. Yakuwarigo is used in writing, but can also be heard in some Anime or other things like plays– it’s used to depict a certain characteristic about the speaker. For instance, a certain type of speech could be used to depict the speaker is old, while other types of speech could be used to depict the speaker is from a certain time period, maybe their gender, or maybe the fact that they’re actually a cat.

Something that should be kept in mind is that yakuwarigo is a type of fictitious speech. If someone in a story speaks a certain way, that doesn’t necessarily mean that’s how some people actually speak or used to speak. Instead, it’s a style purely designed to add some character to what the speaker is saying.

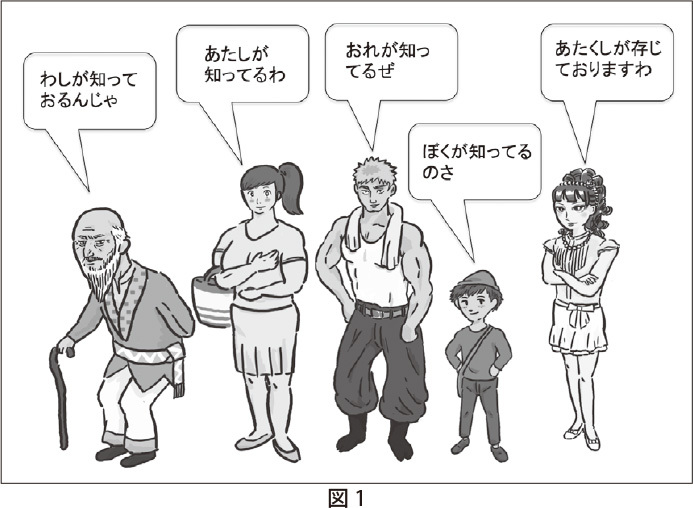

Some forms of yakuwarigo are actually used by real people or based on “real” Japanese however, for example masculine words like おれ, boyish words like ぼく, or feminine words like あたし or the particle ending わ, however these still depict the character of the speaker and could be considered types of 役割語, even though they are also types of actual speech. Breaking the word down, it’s made of 役割 (やくわり), meaning “role”, and 語, meaning “language”. If you put the two concepts you get “role language”, which is an accurate description since it shows what sort of personality or character (the role) the speaker is.

- Old man: わしが知っておるんじゃ

- Feminine woman: あたしが知ってるわ

- Masculine dude: おれが知ってるぜ

- Little dude: ぼくが知ってるのさ

- Well-to-do woman: あたくしが存じておりますわ

Translation: “I know”.

There are plenty of different types of yakuwarigo– here are a few examples of some common ones:

老人語 (ろうじんご) or “old guy talk”

This is widely used to depict someone is elderly, where they have a certain way of speaking. The ending です or だ, becomes じゃ, the verb いる becomes おる, and the pronoun 私 becomes わし, to list a few different usages. If they’re from an older time period especially, they’re probably use ぬ instead of ない, for instance 知らぬ instead of 知らない.

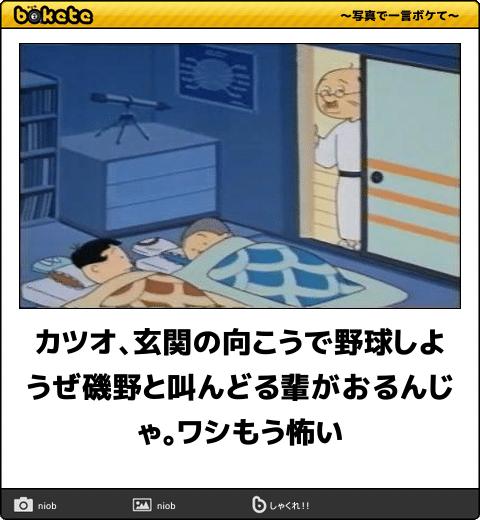

「カツオ、玄関の向こうで野球しようぜ磯野と叫んどる輩がおるんじゃ。ワシもう怖い」

(Katsuo, there’s a kid outside our front door screaming “Let’s play baseball, Isono”. I’m scared.)

Animal or other creature talk

When a speaker happens to be an animal like a cat, or some sort of other creature that doesn’t actually speak in real life, or even if they could, like a robot, they’re often given a sort of “accent” or sentence endings that are simply stuck on to whatever they’ve said. With the robot example, in addition to certain endings that are simply stuck on to the end of whatever they’ve said, their speech will often be in all katakana, showing they have a thick accent. With the cat example, cats will often say にゃん at the end of a sentence which is a type of yakuwarigo. This shouldn’t be confused with onomatopoeia, where にゃん is also the sound a cat makes, like “meow”. If you haven’t read our post on some Japanese animal onomatopoeia, you should check it out! You could get fancy with the accent, for instance a cat could say にゃにをしようかにゃぁ (nyani wo shiyou ka nyaa) instead of なにをしようかな (nani wo shiyou ka na), or そうにゃんだ (sou nyan da) instead of そうなんだ (sou nan da).

「にゃりがとうごにゃいます」 (Nyarigatou gonyaimasu)

アルヨことば or “Chinese accent” talk

This type of yakuwarigo is often used to depict the speaker is Chinese. This is of course completely made up and has nothing to do with how someone with a Chinese language background would speak Japanese. アルヨことば (aruyo-kotoba) was named from あるよ (aru yo), which is a stereotype catchphrase for this type of speech. Another example would be using よろしい (yoroshii) instead of いい (ii), meaning “good”, and generally not using particles or proper tense.

Here is an example:

- アルヨことば: 安いあるよ、早く買うよろしい

- 日本語: 安いんですよ、早く買わないと

- “It’s cheap, you should buy it now!”

「しっ知らないあるよ!」

「しっ知らないあるよ!」

(I- I don’t know!)