It’s common for beginners and sometimes even more advanced students to lack an understanding of how Chinese characters are structured. This includes misconceptions about components and radicals. In this article, I’m going to address some of the misconceptions I have encountered as a teacher and as the “Chinese Guru” here on Skritter. What different kinds of character components are there? What’s a radical?

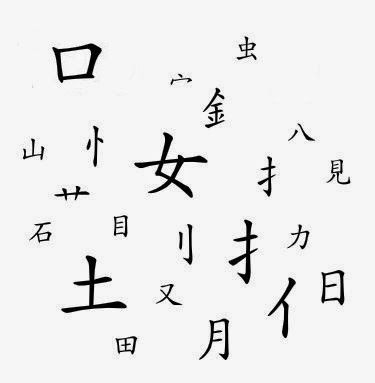

Compound characters and character components

Most Chinese characters are compounds, meaning that they consist of several smaller characters. These may or may not be used as individual characters themselves, it differs from case to case. Characters are typically combined in specific ways and therefore you can’t break them down arbitrarily.

For instance, a character like 想 (xiǎng) “to think” can be broken down first into 相 and 心. Then 相 can be further broken down into 木 and 目. The three characters 心, 木 and 目 can’t be broken down further. This is the only way this character can be broken down, so there is no character that combines 心 with only 木 on top.

There are four major ways of creating compounds, but in this article, I’m going to explore phonetic-semantic compounds, which are the most common type of character (but still the least understood by the average student). Read more about the four main types here.

Meaning and sound

A character component typically has one of two functions: either it carries information about sound (a phonetic component) or it carries information about meaning (a semantic component). To give you a few very basic examples, it should be obvious that in a character like 看 (kàn) “to see”, 目 is related to the meaning of the character (it means “eye”).

It should also be clear that the 马 (mǎ) “horse” in 妈 (mā) “mother” probably isn’t related to meaning. On the other hand, it’s a good guess that it is related to the sound (the pronunciation only differs in tone). The same is true for some other examples that often occur early in textbooks, such as 吗 (ma) “(question particle)” and 骂 (mà) “to scold”. These are unrelated to horses, so 马 component is included to show that the characters have pronunciation similar to 马. A component that carries information about sound is called a phonetic component.

Naturally, I have cherry-picked clear examples here. In some cases, it’s not obvious what function a specific component has and you need to do research into character etymology or the pronunciation of older forms of Chinese to make sure. Perhaps they sounded the same thousands of years ago, but not any longer. Some characters are very reliable, though, check some examples here. If you want to know more about how you should use phonetic components to learn characters, read more here: Phonetic components, part 1: The key to 80% of all Chinese characters.

Radicals

Now let’s turn to radicals, which are misunderstood by a majority of students. To understand what they are and how they work, we need to look at how Chinese dictionaries are structured. Traditionally, Chinese dictionaries aren’t sorted alphabetically, but instead use what’s called 部首 (bùshǒu) in Chinese, meaning “section head”. For some reason, this is translated as “radical” in English.

Each Chinese character has one and only one radical, which dictionaries use to sort the character into the right section. The exact number of radicals varies. In the most recent edition of 现代汉语词典, there are 201. Another standard reference for radicals is the Kangxi dictionary published in 1716 which contains 214 radicals. Not all characters are sorted by exactly the same radical in all dictionaries, but most are. Within each section, characters are sorted by the number of additional strokes necessary to write the character, not including the radical.

So, a radical is a part of a character that happens to have a special function used in dictionaries. It’s not the same as a character component, it’s not even the same thing as a semantic character component. As far as dictionaries are concerned, radicals are the part of a certain character that is used to index it, nothing more, nothing less. This means that a certain character component, say 土 (tǔ) “earth”, can be the radical in some characters like 境 (jìng) “situation”, but not in others such as 肚 (dù) “stomach”. What kind of information do you think 土 carries in 肚?

Why all the fuss about radicals, then?

If radicals are so limited, how come that everyone seems to talk about them and use them for teaching Chinese? Part of the reason is that many haven’t understood the difference between radicals and character components in general, which is evident when you hear someone say that “this character contains two radicals, 木 and 目”. No character contains two radicals, that would defy the purpose of radicals!

Character components, on the other hand, are very important to understand how characters are structured, but the radicals themselves aren’t useful unless you want to look up characters in old dictionaries. Thus, pay attention to components and what function they have.

That being said, many of the radicals also happen to be very common semantic components, so it’s sometimes convenient to use radicals as a proxy for semantic components. I have done this myself when creating a list of the 100 most common radicals. You can study this list on Skritter too:

The point isn’t that they are radicals, it’s that they also happen to be common semantic components. This is a simplification, though, and there are many common semantic components that aren’t radicals. Unfortunately, there is no good overview of these, as far as I know.

Conclusion

I hope this article has helped you to understand the difference between different kinds of character components on the one hand and radicals on the other. If you still have questions, please leave a comment!