Have you ever looked at Chinese calligraphy and marveled at its beauty, even without knowing the language? It’s a dynamic and ancient art form, and with a little background, anyone can learn to appreciate its elegance and history.

Today, we’re going to introduce you to the art of Chinese calligraphy. The Chinese word for it is 书法 (書法) shūfǎ, which literally translates to “the method of writing.” We’ll explore the five core styles, looking at their evolution and unique characteristics to give you a deeper insight into this fascinating tradition.

In Chinese calligraphy, the five basic script styles are known as the “Five Scripts” or 五体 (五體) wǔ tǐ. These styles are Seal Script, Clerical Script, Cursive Script, Running Script, and Standard Script. All other styles you might encounter are simply branches that have evolved from these five pillars.

Seal Script – 篆书 (篆書) zhuàn shū

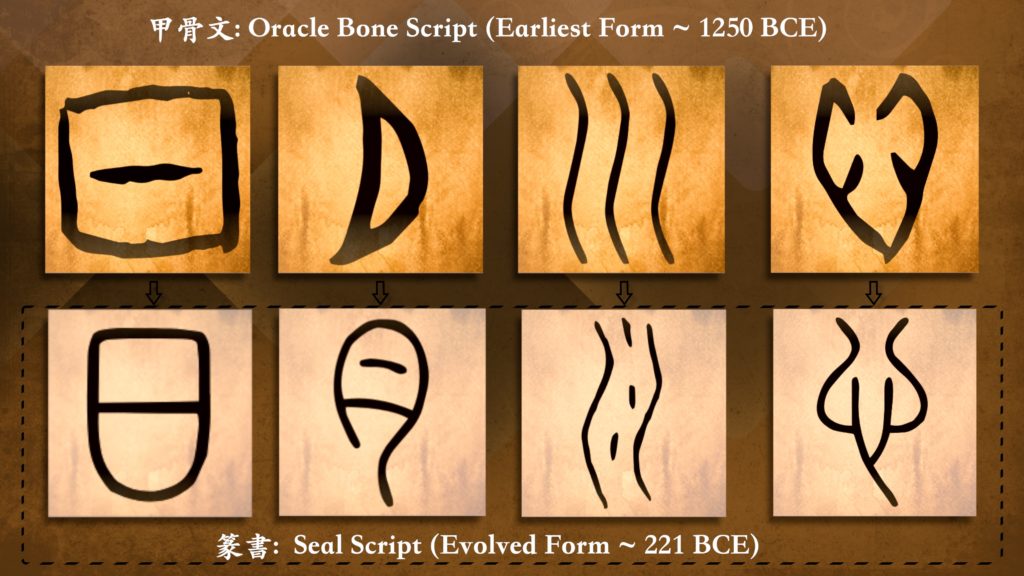

Let’s start with one of the earliest forms of Chinese writing, 篆书 (篆書) zhuàn shū. You can think of this style as the one closest to nature, using simple pictograms to “draw” what it describes. It’s named Seal Script because these characters were often carved into official seals or stamps used for authentication by nobility and government in ancient China.

Seal Script has the simplest strokes of the five styles, emphasizing left-to-right symmetry and using mainly curves and dots with no sharp corners. Because it looks so much like a drawing, it can be difficult for even native speakers to recognize. However, this is also why it’s so easy for non-Chinese speakers to appreciate its artistic qualities! A famous form of Seal Script is 甲骨文 (jiǎ gǔ wén), or Oracle Bone Script—the earliest known Chinese writing system, which was carved onto turtle shells.

Let’s look at a few examples. Can you see the little drawings in them?

- 日 rì (sun)

- 月 yuè (moon)

- 川 chuān (river)

- 心 xīn (heart)

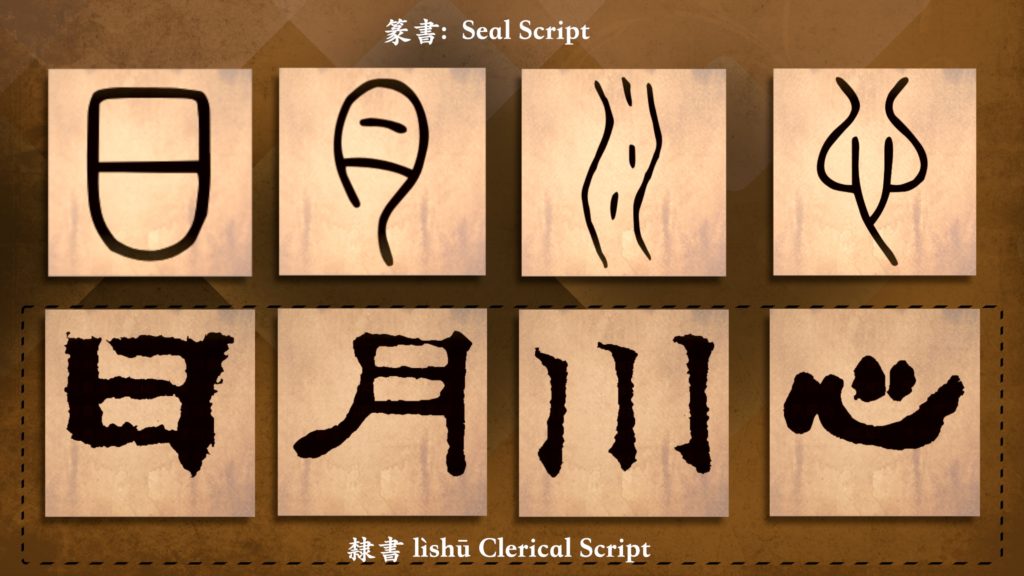

Clerical Script – 隶书 (隸書) lì shū

Next, let’s look at the style that developed after Seal Script: 隶书 (隸書) lì shū. There’s a saying that captures the difference perfectly: 「篆如画,隶如波。」(「篆如畫,隸如波。」) zhuàn rú huà, lì rú bō — “Seal script is like a painting, and Clerical script is like a wave.”

If Seal Script is like a child’s first drawings, Clerical Script is when that child begins to create structure, order, and style. This script is typically more flattened, and its most recognizable feature is its horizontal strokes, which flow with a “wave-like” rhythm.

Linguistically, Clerical Script marks the transition from pictographs to more abstract symbols. You begin to see more straight lines; horizontals are horizontal, and verticals are vertical. Take the character for home, 家 jiā, for example. In Seal Script, you can still see the image of a pig under a roof. In Clerical Script, that imagery has faded.

Why is it called Clerical Script? After the Qin Dynasty, the volume of government documents increased rapidly. To improve efficiency, strokes were simplified and standardized. The people responsible for copying these documents were often scribes or servants, called 隶 (隸) lì, which gave the script its name.

Let’s look at our examples again. They feel more like characters than pictures now, don’t they?

- 日 rì (sun)

- 月 yuè (moon)

- 川 chuān (river)

- 心 xīn (heart)

Standard Script – 楷书 (楷書) kǎi shū

After Clerical Script came the parallel development of Standard, Running, and Cursive scripts—like three siblings, each with their own distinct personality.

Let’s start with 楷书 (楷書) kǎi shū, as it’s the most common style seen today. Most printed Chinese fonts, like the 标楷体 (標楷體) biāo kǎi tǐ typeface we use in the Skritter app, are based on this script. Its main feature is its square and upright structure. If you’re learning Chinese, this is likely the script you’re most familiar with from your textbooks.

The famous Song Dynasty calligrapher 苏轼 (蘇軾) Sū Shì once said: 「真如立,行如行,草如走。」(「真如立,行如行,草如走。」) zhēn rú lì, xíng rú xíng, cǎo rú zǒu — “Standard Script is like standing, Running Script (semi-cursive) is like walking, and Cursive Script is like running.”

This reflects both the posture and the speed of writing. 楷书 (楷書) kǎi shū, also known as 真书 (真書) zhēn shū (“True Script”), has a strong sense of order. Its golden age was during the Tang Dynasty, whose values of structure and order were famously reflected in its capital city’s chessboard-like design. This is why it remains the preferred script for official documents and modern text.

Here are the examples in their structured, angular form:

- 日 rì (sun)

- 月 yuè (moon)

- 川 chuān (river)

- 心 xīn (heart)

Running Script/Semi-cursive – 行书 (行書) xíng shū

The character 行 xíng means “to walk” or “to travel.” As its name suggests, 行书 (行書) xíng shū is like taking a stroll while writing. It’s slightly more relaxed and faster than Standard Script but is still easily recognizable.

This is the script most commonly used in daily life for things like taking notes or signing names. Native speakers often simplify strokes or connect them, which gives Running Script its unique character. Its flexibility has led to many distinct styles, making it a favorite among famous calligraphers and arguably the most technically demanding script to master.

Let’s see our examples in a more fluid style:

- 日 rì (sun)

- 月 yuè (moon)

- 川 chuān (river)

- 心 xīn (heart)

Cursive Script – 草书 (草書) cǎo shū

Let’s return to Su Shi’s quote: “Cursive Script is like running.” In ancient times, the character 走 zǒu actually meant “to run.” Cursive Script, or 草书 (草書) cǎo shū, is written the fastest and is the most difficult to read, even for native speakers.

But don’t mistake its speed for sloppiness! There’s a conventional system of forms called 草法 cǎo fǎ (“Cursive Method”) that learners must memorize. In fact, many modern simplified Chinese characters originated from these cursive forms.

Of all the five styles, Cursive Script is the most expressive and emotional. It’s a dynamic art full of rhythm and personality, often seen as a form of emotional release. Many calligraphers would even write in this style while drinking wine to help free their spirit and hand. It’s raw, improvisational, and explosive.

Imagine holding a brush and writing these characters with speed and emotion:

- 日 rì (sun)

- 月 yuè (moon)

- 川 chuān (river)

- 心 xīn (heart)

Conclusion

From the pictorial Seal Script to the expressive Cursive Script, each of the five core styles of calligraphy offers a unique window into Chinese culture and history. We hope this quick tour helps you feel the rhythm, movement, and powerful beauty of this incredible art form.

If you’d like to try writing Chinese characters yourself, consider using our app, Skritter! The main canvas uses a version of 楷书 (楷書) kǎi shū because it’s best for learners, but you can also practice 行书 (行書) xíng shū by switching to self-grading mode.

And if you want to dive deeper, the book Understanding Chinese Calligraphy 认识书法 (認識書法) rènshì shūfǎ by Fang Jianxun is an amazing resource.

Key Vocabulary

| Simplified / Traditional | Pinyin | English |

| 书法 / 書法 | shūfǎ | Calligraphy (“method of writing”) |

| 五体 / 五體 | wǔ tǐ | The Five Scripts / The Five Styles |

| 篆书 / 篆書 | zhuàn shū | Seal Script |

| 隶书 / 隸書 | lì shū | Clerical Script |

| 楷书 / 楷書 | kǎi shū | Standard Script |

| 行书 / 行書 | xíng shū | Running Script |

| 草书 / 草書 | cǎo shū | Cursive Script |

| 甲骨文 | jiǎ gǔ wén | Oracle Bone Script |