Picture this: you’re watching a Chinese historical drama. One character calls someone 孔明 (Kǒngmíng), another calls the same person 諸葛亮 (諸葛亮, Zhūgě Liàng), and a third refers to 臥龍先生 (卧龙先生, Wòlóng Xiānshēng). You soon realize they’re all talking about the same guy!

If you’ve ever been confused by the multiple names ancient Chinese figures had, you’re not alone. Today, we’re diving into the fascinating world of ancient Chinese naming systems. By the end, you’ll understand why calling someone by their birth name was a major insult and how one person could have up to five different names.

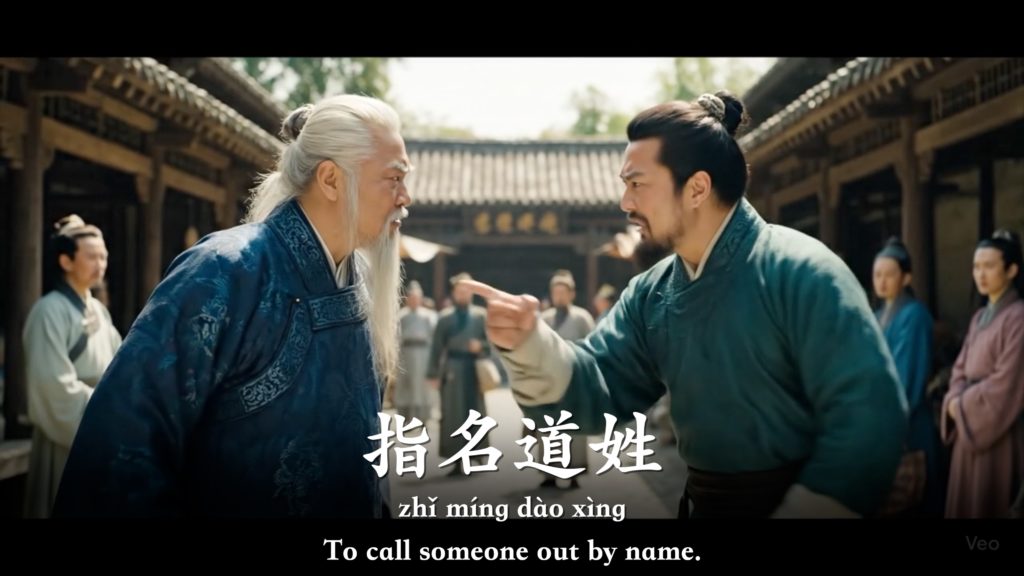

A famous Chinese idiom, 指名道姓 (zhǐ míng dào xìng), means to publicly criticize someone by name. In ancient times, this was considered incredibly rude, something even sworn enemies would avoid. Why? Let’s find out.

The Evolution of Surnames: From Mothers to Fathers

When learning Chinese, you likely learned to ask, “你姓什麼?(你姓什么?, Nǐ xìng shénme?)” (What’s your surname?). But the story behind Chinese surnames, or 姓氏 (formal term) (xìngshì), is more complex than you might think. Originally, 姓 (xìng) and 氏 (shì) were two different things.

姓 (Xìng) — The Mother’s Mark

Look closely at the character 姓. It’s composed of two radicals: 女 (nǚ), meaning “woman,” and 生 (shēng), meaning “to give birth.” It literally meant “born of a woman.” In early Chinese history, society was matrilineal. Children belonged to their mother’s clan because maternity was certain, while paternity could be ambiguous.

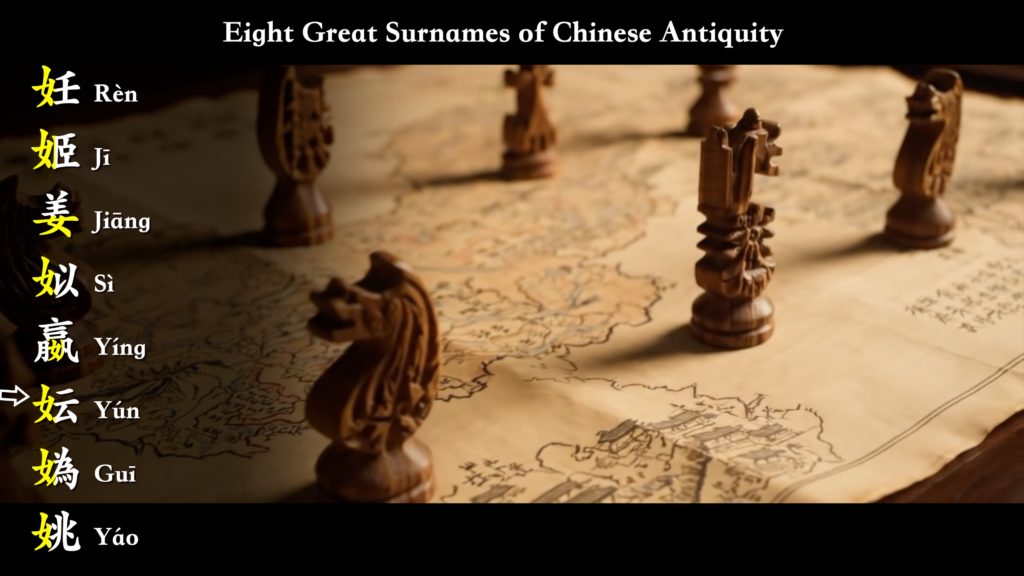

This is why the eight great ancestral clan names all contain the 女 radical: Your 姓 identified your maternal bloodline.

氏 (Shì) — The Father’s Legacy

As society shifted towards a patriarchal structure, the 氏 (shì) emerged to represent the father’s lineage or noble house. They weren’t about bloodlines but about tribal leadership and social status.

By the Warring States period, this complex system simplified. The aristocracy declined, the 氏 lost its distinct meaning, and everything merged into the 姓. That’s why we use 姓氏 in formal contexts but just 姓 in daily conversation today.

Study the deck on Skritter. Download our app on iOS or Google Play. Open Directly in Skritter here.

The Many Names of One Person

In ancient China, a single person could have up to five different names. Let’s break them down.

1. 名 (Míng) — The Family’s Secret

The character 名 (míng) shows a mouth (口) calling out in the evening (夕), literally “to call one’s name at night to identify yourself.” This was your birth name, used only by family and elders. Surprisingly, these names were often deliberately plain or even crude, as beautiful names were believed to attract bad luck.

For example:

- Duke 周桓公 (周桓公, Zhōuhuán Gōng) was named 黑肩 (Hēijiān), or “Black Shoulder.”

- Duke 晉成公 (晋成公, Jìnchéng Gōng) was named 黑臀 (Hēitún), or “Black Buttocks.”

2. 訓名/學名 (Xùnmíng/Xuémíng) — The School Name

When a child started school, they often received a 訓名 (xùn míng) or 學名 (xué míng), a more respectable name for public use.

3. 字 (Zì) — The Respect Name

At around age twenty (or marriage age for women), a person received a 字 (zì), or courtesy name. Peers and juniors used this name to show respect. Using someone’s 名 (míng) was a grave insult, but using their 字 (zì) was the polite standard.

Often, the 字 was cleverly connected to the 名:

- Synonyms: 諸葛亮 (Zhūgě Liàng), 字 孔明 (Kǒngmíng). Both 亮 and 明 mean “bright.”

- Antonyms: 韓愈 (韩愈, Hán Yù), 字 退之 (Tuìzhī). 愈 means “to advance,” while 退之 means “to retreat.”

4. 號 (Hào) — The Creative Expression

Finally, there was the 號 (hào), which was like an ancient Chinese username or alias. It was self-chosen and could be poetic or whimsical.

- The poet 陶淵明 (Táo Yuānmíng) called himself 五柳先生 (Wǔliǔ Xiānshēng), or “Mr. Five Willows,” after the trees near his home.

- The scholar 歐陽修 (欧阳修, Ōuyáng Xiū) was 六一居士 (Liùyī Jūshì), “The Hermit of Six Ones,” for his collection of books, inscriptions, a lute, a board game, a pot of wine, and himself.

The Ultimate Insult: Calling Someone Out

Now we can understand why 指名道姓 (zhǐ míng dào xìng) was so offensive. During the Three Kingdoms period, 曹操 (Cáo Cāo) had slaughtered the family of 馬超 (马超, Mǎ Chāo). Despite his immense hatred, when recounting the tragedy, 馬超 would say, “孟德 (Mèngdé) killed my entire family,” using 曹操‘s respectful 字 rather than his 名. This displayed his noble character even in rage.

Using someone’s 名 in public was to declare them beneath respect. Shouting their full name (姓 + 名) was an open challenge. This cultural echo persists today, where using a person’s full name can sound aggressive.

Key Vocabulary

| Simplified | Traditional | Pinyin | English |

| 指名道姓 | 指名道姓 | zhǐ míng dào xìng | To criticize someone by name |

| 姓氏 | 姓氏 | xìngshì | Surname (formal) |

| 姓 | 姓 | xìng | Surname (common) |

| 氏 | 氏 | shì | Clan name/lineage (archaic) |

| 名 | 名 | míng | Given name (used by elders) |

| 字 | 字 | zì | Courtesy name (used by peers) |

| 號 | 号 | hào | Alias/Style name (self-chosen) |

Understanding these traditions reveals deep insights into Chinese culture—the importance of respect, social hierarchy, and the power of language. The next time you watch a historical drama, you’ll be able to appreciate the rich complexity behind every character’s name.