Welcome to the ultimate guide to Chinese character stroke order! If you’re new to Chinese and just want the most essential information, the Chinese character stroke order 101 is for you.

Chinese character stroke order 101: What every student needs to know

Chinese characters are written with a number of distinct strokes, and when writing characters, there is generally a fixed order in which these strokes are written.

Clicking on character illustrations and animations in this article will let you practise writing them on screen!

Following this order makes characters easier both to learn and write!

Here are 5 things every student needs to know about stroke order:

- Stroke order is based on a few easy-to-learn principles, the most important being that characters are written from top to bottom, and left to right

- Learning stroke order is good because it makes it easier to write, enables you to use handwriting input, and makes it easier to read other people’s handwriting

- Beginners should learn stroke order, either by looking it up or by learning characters in apps like Skritter

- Stroke order feels hard at first, but ceases to a problem later

- There are sometimes more than one correct way of writing a character; which standard you follow doesn’t matter, but don’t make up your own

The Ultimate Guide to Chinese Character Stroke Order

Here’s our complete guide to Chinese character stroke order:

-

- Eight stroke order rules for writing Chinese characters

- One rule to rule them all: Top left to bottom right

- Stroke order explained using only the most common characters

- Learning by writing

- Stroke-order rule #1: Top to bottom

- Stroke-order rule #2: Left to right

- Stroke-order rule #3: Left-sloping stroke before right-sloping stroke

- Stroke-order rule #4: Horizontal strokes before crossing vertical stroke

- Stroke-order rule #5: Framing strokes before box contents, but closing stroke last

- Stroke-order rule #6: Skewering stroke last

- Stroke order rule #7: Symmetrical additions last

- Stroke-order rule #8: Additional dots last

- Mastering the Chinese character stroke order rules

- Practice stroke order on your phone for free!

- Standards and variation in stroke order for writing Chinese characters

- Do you have to learn the stroke order for every Chinese character you learn?

- Chinese characters are easier to write when you use the right stroke order

- Chinese characters written with the wrong stroke order don’t look the same

- Learning correct stroke order makes it easier to understand other people’s handwriting

- Using correct stroke order makes it easy to look up Chinese characters you don’t know

- There’s no good alternative to using correct stroke order when writing Chinese characters

- Follow a standard; which one doesn’t matter that much

- How to learn the stroke order of Chinese characters

- More about the strokes used to write Chinese characters

- Chinese character stroke order resources

- Eight stroke order rules for writing Chinese characters

2. Eight stroke order rules for writing Chinese characters

Think of these stroke order rules as rules of thumb, not strict laws for how characters have to be written. The main reason you want to write this way is that it’s easier in the long run, not because someone forces you to!

Stroke order rules can contradict each other. Some sources give you nine rules, others seven, but the underlying principles are the same.

Below, we present eight have selected eight stroke order rules that we think cover everything you need as a student!

One rule to rule them all: Top left to bottom right

If you only want one rule for stroke order, then remember that characters are typically written from the top left to the bottom right:

Stroke order explained using only the most common characters

In difference to other guides to stroke order in Chinese, this one does not assume that you know anything in advance, so the rules and examples can be understood only based on the previous rules.

The examples here are also limited to only characters from the top 100, so you can safely learn all these characters without feeling you’re doing it only to learn stroke order!

Learning by writing

For maximum effectiveness, you should write these characters as you go through the stroke order rules. To help you, we have created a video that goes through all these rules in a clear and pedagogical manner.

In our app, you can watch the video and write all these characters on screen with corrective feedback, completely for free! You don’t even need an account to try it out.

If you’d rather use pen and paper, that works too. The video is available on YouTube here, so you can follow along without the app if you prefer.

To practice the stroke order rules outside the app, click the animations below to write on your computer or phone. Click the image below to test writing the character shown!

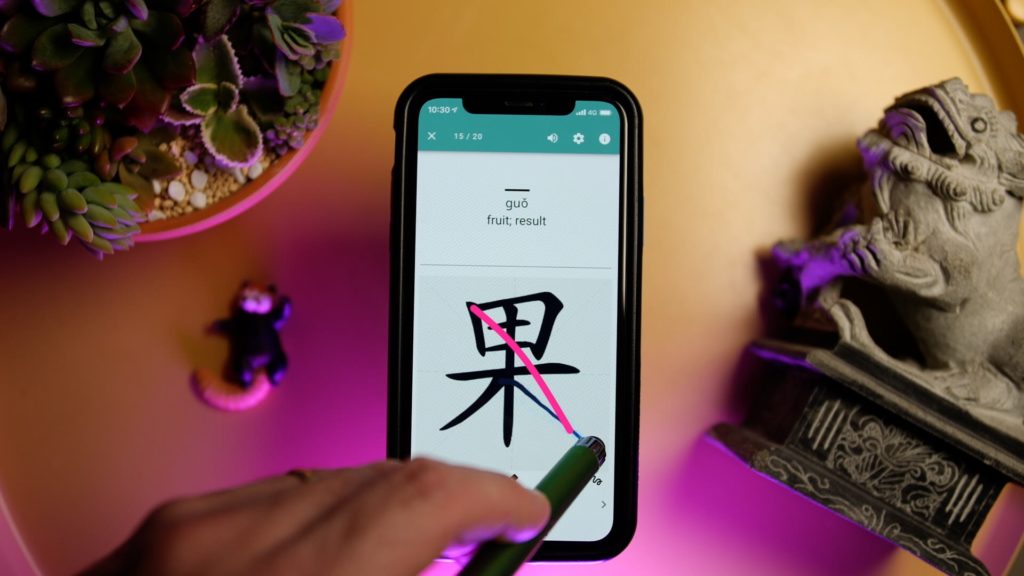

Characters are in general written from top to bottom and from left to right. This is 果, guǒ, “fruit; result”. Click the image to try writing it on screen!

In general, Chinese characters are written from top to bottom, left to right. This means that you normally begin in the very top left corner and work your way down to the bottom right corner.

Stroke-order rule #1: Top to bottom

Let’s look at three characters that demonstrate this rule. You write them all from top to bottom:

二 èr “two”

Click to practise writing the character!

Click to practise writing the character!

三 sān “three”

Click to practise writing the character!

工 gōng “work”

Click to practise writing the character!

Stroke-order rule #2: Left to right

Most Chinese characters are made up of building blocks called components. In general, we write one component before moving onto the next. In this section, we have two characters like this.

First, complete the left part, and then the right, and remember, its top to bottom, and then left to right. In the last case, the dots are written from left to right.

行 xíng “to walk”

作 zuò “to do; to make”

立 lì “to stand”

Stroke-order rule #3: Left-sloping stroke before right-sloping stroke

For this rule, we write left-sloping strokes before right-sloping strokes:

人 rén “person”

八 bā “eight”

文 wén “language; script”

Stroke-order rule #4: Horizontal strokes before crossing vertical stroke

Horizontal strokes are generally written before crossing vertical strokes. For example, with 十 (shí)”ten”, you do the horizontal first.

十 shí “ten”

For 大 (dà), “big”, we write the horizontal stroke first as well and then finish off the character using rule #3 (left downward stroke before right downward strokes).

大 dà “big”

The same goes for 天 tiān “sky; day”:

天 tiān “sky; day”

Stroke-order rule #5: Framing strokes before box contents, but closing stroke last

The most basic framing component is 囗 (wéi), “enclosure”, which shows just that, an enclosure. First, we write a top to bottom stroke (rule #1), then draw the top right corner, and finally, we finish it off by closing out the bottom. Writing the bottom stroke last like this is common in other types of characters, too.

囗 wéi “enclosure”

The same stroke order applies to the character 口 (kǒu), “mouth; opening”, which means mouth but is technically not a framing component. If anything appears in a square like this, you know it’s 囗 (wéi), “enclosure”, because 口 (kǒu), “mouth; opening” doesn’t have other components inside of it.

口 kǒu “mouth; opening”

A good example of this is 因 (yīn), “reason”, which shows 大 (dà), “big”, inside of 囗 (wéi), “enclosure”. Note that all strokes of the enclosure except the last one are written, then the contained component is written, then the closing last stroke.

因 yīn “reason”

The character for “sun; day”, 日 (rì), follows a similar pattern, with the final stroke closing it all off.

日 rì “sun; day”

Stroke-order rule #6: Skewering stroke last

What this means is that if there is a vertical stroke that cuts through the character, you generally write it last. So the character 中 (zhōng), “middle”, gets skewered right at the end, after the box is completed.

中 zhōng “middle”

To write 半 (bàn), “half”, we go top to bottom, left to right, and finish off with a skewering final stroke.

半 bàn “half”

手 (shǒu), “hand”, is also written with the skewering stroke last. Note that the first stroke is right-sloping stroke. It’s quite rare for strokes in Chinese characters to go upwards

手 shǒu “hand”

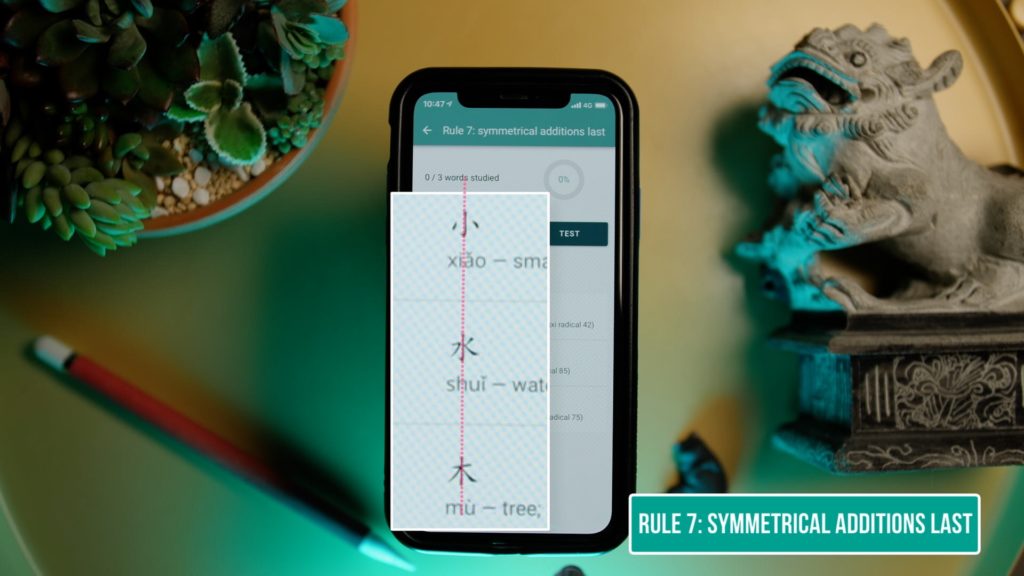

Stroke order rule #7: Symmetrical additions last

Take a look at these three characters. They all have some element of symmetry. First, we begin with the central stroke, then we move from left to right, finishing off with the symmetrical addition last.

So with 小 (xiǎo) “small”, we start in the middle and end with the final symmetrical additions.

小 xiǎo “small”

The same goes for 水 (shuǐ) “water”, even if the additions are not perfectly symmetrical.

水 shuǐ “water”

The writing of 木 (mù), “tree; wood”, can be explained with the symmetrical additions last, along with the left-sloping strokes before right-sloping strokes rule.

木 mù “tree; wood”

Alert students might have spotted a contradiction here: 半 (bàn), “half”, does have symmetrical dots, but they are not written last!

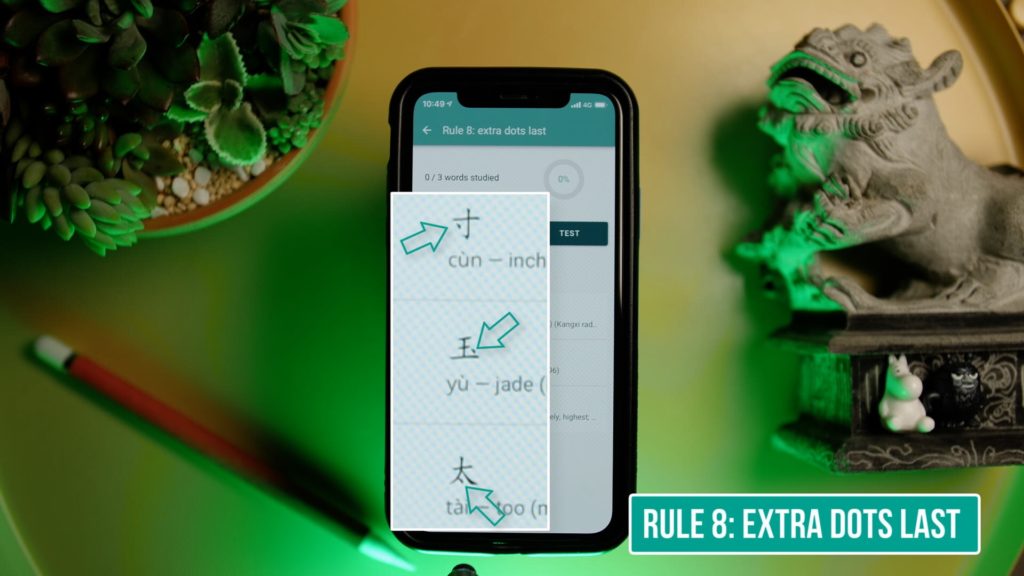

Stroke-order rule #8: Additional dots last

These three characters all have one thing in common: They have an extra dot that is written last.

寸 cún “inch”

玉 yù “jade”

太 tài “too (much); excessive”

Mastering the Chinese character stroke order rules

Now that you know the basic principles, you will be able to write most characters!

If you write characters in Skritter, we will automatically show you the right way to do it. If you want to study stroke order for a specific character, you can tap on the teaching button or long-press on the screen to show the next stroke. If you keep getting it wrong, we will show you the correct one as well.

Over time, these rules will become more and more natural, and since Skritter uses a smart system to schedule reviews, we will show the ones you get wrong more often to ensure you don’t forget them!

Practice stroke order on your phone for free!

In the final section of this free deck in Skritter, we have put together a list of common characters that have various combinations of these stroke order rules. You can use this deck to test your newly earned skill or use it to practice more to reinforce what you have learned. Try it out now!

3. Standards and variation in stroke order for writing Chinese characters

The earliest Chinese characters don’t show a clear stroke order, but as the writing system developed, writing became more standardized. Early writing that survives to this day is often in the form of carvings on hard surfaces, such as bones and bronze, and it should be clear that writing on paper is quite different from carving in bronze. Unfortunately, paper deteriorates quickly, so even if the Chinese started writing on paper a very long time ago, we don’t actually know much about how these characters were written.

When studying the stroke order principles described above, and especially when trying them out in practice with real characters, it’s obvious that different rules sometimes conflict with each other. Chinese characters are also much too complex to allow a simple set of rules to describe exactly how each character should be written.

The standards for stroke order have developed organically over time according to the needs and preferences of those who use the characters. This has lead to the development of several different standards. It would be unreasonable to think that one single standard could be imposed on everyone who writes Chinese characters, especially considering that characters are used in other languages, most notably Japanese.

Chinese learners will encounter several different standards for stroke order, so it’s good to know about them!

It’s hard to argue that a certain standard is better than another, but if you care about being formally correct, you do need to be aware of what standard you’re using. If you study Chinese in a formal setting, your teacher, school or curriculum might also have decided what standard you should follow.

If you don’t care that much, just try to follow the stroke order rules set out above. When you’re not sure, look the character up in a dictionary that follows the standard that suits your needs best. Next, we will look at how to look up stroke order!

Different standards for Chinese character stroke order

There are four major standards for stroke order: mainland China, Taiwan, Hong Kong, and Japan. Most characters are written the same in all standards, so don’t be alarmed when you see different stroke order here; we have deliberately chosen examples that are different!

-

Mainland China – This is the standard for simplified Chinese characters and the one most students will follow. Unfortunately, the authoritative publication for this standard is not available in an easily searchable digital format. It’s called 现代汉语通用字笔顺规范 and can be downloaded as a PDF here. However, most modern electronic dictionaries are reliable when it comes to stroke order, so you normally don’t need to refer to 现代汉语通用字笔顺规范. Skritter follows this standard for simplified characters, but if you want to look something up online, check out 汉字屋 – 汉字笔顺. To search, for a character, just type or paste it in the search box! On the right, you can see the character 必 bì “must“, which is a good example character because stroke order differs between standards.

Mainland China stroke order animation by Cangjie6.

-

Taiwan – If you’re learning traditional characters and studying Mandarin, you probably want to follow the standard used in Taiwan. This is easy to access through the Ministry of Education’s official website and app (iOS and Android); just search for any character and click the pencil symbol and you will see animated stroke order.

Taiwan and Hong Kong stroke order animation by Cangjie6.

- Hong Kong – The second option if you’re learning traditional characters is Hong Kong standard, which differs from Taiwan in some cases (although not the one shown here). If you want to look something up, you can check the official website. Few students of Mandarin will use this standard for traditional characters, but it’s good to know that it exists.

-

Japan – This article is meant to deal with stroke order for students of Chinese rather than Japanese, but it’s good to know that the way characters are written in Japanese sometimes differ from how they are written in Chinese. Read more about the differences in how characters are written in Chinese and Japanese in this article.

Japanese stroke order animation by Cangjie6.

As we said above, the differences between these standards are often to be found when basic principles conflict with each other and there’s no objective reason to say that one is better than the other.

Stroke order variations within the same standard

We now know that a character can be written differently in different regions, but in some cases, the same character can be written differently depending on context.

This usually makes sense, because it makes the character easier to write, but can still be confusing.

Two examples are the characters 车 chē, “vehicle”, and 牛 niú, “cow; ox”.

If you know some Chinese already, how do you write these characters? More specifically, is the last stroke horizontal or vertical? What about if you write them on the left of other characters, such as 轻 qīng, “light” or 特 tè, “special”?

Well, for the stand-alone characters, the answer is that the last stroke is vertical:

This is also the case when they appear in other characters where they retain their original proportions, such as in 军, 连, 牢 and 牵.

However, when they appear in their slightly altered left-of-character component form (偏旁), they aren’t written the same way. Instead, the order of the two last strokes is reversed, so the last stroke is horizontal. Like so:

轻 qīng, “light”

特 tè, “special”

It should be noted that this is relevant for traditional characters too, but only for 牛, since 车 is written 車 in traditional, which doesn’t acquire the alternate form with an upward stroke and is therefore always written with the vertical stroke last according to the rule about skewering strokes.

Why this difference? Try it yourself!

If you try the two variants yourself (click the animations above or try it on paper), it’s not hard to understand why they are written differently.

The upward stroke that should end the slightly squeezed variants are only one part of the character and whatever part follows it will be written from the top down, so it’s the natural direction to take after finishing the first component.

Compare with 扌(the vertical version of 手 shǒu “hand”), which has a similar feel to it, very likely for the same reason. That one is not as easy to be confused by because it looks more different already. It’s even called 提手旁 in Chinese, where 提 means “lift” and is the name of the upward stroke.

Don’t be confused, let Skritter guide you!

Don’t be confused when you see the stroke order change in Skritter or elsewhere! It’s not the case that some sources say you should use one stroke order over the other, it simply depends on the character you’re writing.

In particular, it’s determined by where in the character the component appears and what makes fluid writing easy.

Do you have to learn the stroke order for every Chinese character you learn?

Yes and no.

Yes, you need to care about stroke order when you write characters, but no, you don’t need to learn it separately for each character.

After a while, stroke order will feel natural and once you’ve learned a few hundred characters, you won’t really have to spend time learning the stroke order of most characters you encounter.

Sure, there will be exceptions, but not that many! And if you end up writing a rare component incorrectly, few people will care.

But why do you need to learn stroke order? Can’t you just write characters any way you want and just not care about what some official publication says?

You can, but the general consensus among people who teach Chinese is that you should care. We don’t say this to make your life difficult; we say it because we think it’s the easiest way in the long run.

Not convinced? Read on!

Chinese characters are easier to write when you use the right stroke order

As we have seen, stroke order exists because it’s practical. The standard stroke order reflects the most efficient way of writing.

Sometimes, this doesn’t feel right for beginners, but you have to take into consideration that the few characters you have written are not necessarily a representative sample of the written language.

In other words, some rules make sense when applied to the language as a whole, not necessarily every single case.

Furthermore, while you might prefer a different way of writing a character as a beginner, you might simply be wrong. That feeling is based on a limited experience of writing characters, so wouldn’t it make more sense to trust the trillions of hours Chinese people have spent writing their own language? We think it does!

In addition, we actually have stroke order rules in English, too, for the same reason. You don’t write the letter “l” from the bottom up, do you? Few people cross their “t” from right to left.

Even though not every single case might make sense, in general, stroke order rules still make writing by hand easier.

Chinese characters written with the wrong stroke order don’t look the same

It might surprise you that an experienced Chinese teacher can see if you use the correct stroke order or not based on a written assignment, even if he or she does not observe you when you write.

The reason is that even if you might think that the end result is the same no matter what order you write the strokes, this is not true!

Sure, if you write every single stroke slowly and carefully, you could arrive at the same end result, but the whole point of stroke order is to allow for fast and accurate writing.

One day, you will want to write faster, and that means that strokes will occasionally be joined together. If you join strokes the way native speakers do, your writing will begin to approach that of a native speaker: no one will find it hard to read.

But if you make up your own stroke order and start joining strokes that no native speaker would, people will struggle to decipher your characters.

Learning correct stroke order makes it easier to understand other people’s handwriting

Learning to read other people’s handwriting in Chinese is not easy.

If you don’t know about stroke order, it will be hard to figure out which strokes are actually joined together when native speakers write. While you can get away with very little handwriting in a modern, digital society, avoiding other people’s handwriting is much harder.

Naturally, knowing about stroke order is not enough to read handwritten Chines,e but it is one of the necessary steps. If you want to learn more about learning to read handwritten Chinese, check out this article:

Using correct stroke order makes it easy to look up Chinese characters you don’t know

If you want to look up a printed or handwritten Chinese character you don’t know, the quickest way is to use handwriting recognition on your phone or computer.

On your phone, just add Chinese language input and make sure to enable handwriting. You can also use dictionary apps like Pleco or Hanping that have handwriting recognition. On your computer, you can use websites like LINE Dict to draw with your mouse (just click the pencil symbol next to the search box).

When you write on screen, your computer or phone will try to decide which character you most likely intended to write. It will use different data for this, but stroke order is an important one.

If you write a simple character with the wrong stroke order, or even worse, with the wrong number of strokes, it will often fail.

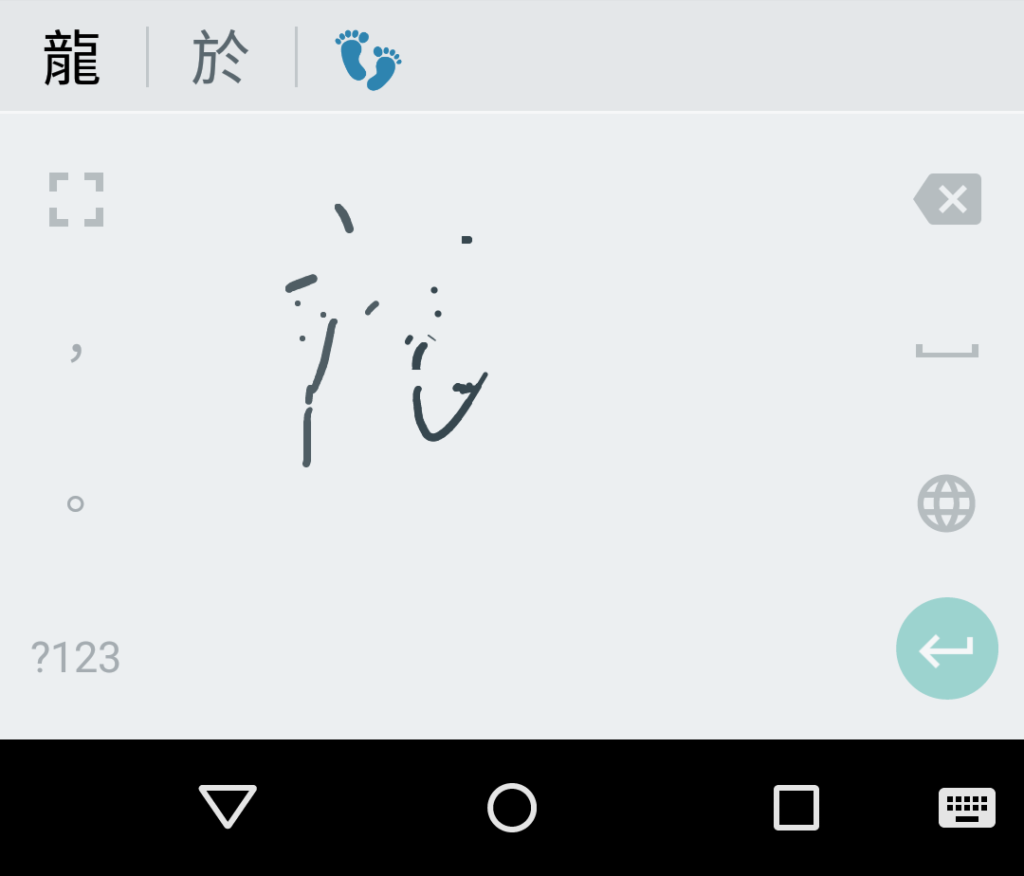

However, if you write the right number of strokes in the right order, it will often succeed, even if the character is completely unreadable for a human. Check this example of the traditional character 龍 lóng “dragon”:

A human would struggle to read that, but the dictionary still guessed it correctly, because the stroke order was right. This is the handwriting input in Pleco, by the way.

There’s no good alternative to using correct stroke order when writing Chinese characters

Let’s look at the alternative to adhering to correct stroke order, which would be improvising stroke order or inventing your own rules.

There is no long-term advantage in doing this.

Even though you think that your version is better, that assessment is based on your very limited knowledge of Chinese. Are you sure you will still think it’s better after writing characters for a year?

Creating a consistent system on your own will be hard in itself, so if you’re going to write with a consistent stroke order, why not get it right from the start?

The reason you want to write characters the same way every time is of course that muscle memory matters! The more you write a character, the more likely it is that you will remember how to write it without thinking too much about it. Naturally, this is not always enough, but it helps. If you’re going to write longer texts by hand, this is a must.

Of course, if you care about penmanship, you have to write the same way every time, otherwise, you won’t improve much.

Follow a standard; which one doesn’t matter that much

If you learn to write in a certain way from a reliable source such as a dictionary or a competent teacher, you can safely ignore other variants if you want. As long as you follow a standard, you should be okay; it doesn’t matter which standard you follow.

We saw that the character 必 was written differently above. Another example is the three strokes in 忄 (the vertical radical version of 心, “heart”), which can be written in several ways. It matters little which of these you use.

If you really want to know, the Mainland standard is dots first, then vertical stroke; Taiwan standard is left to right (dot, vertical, dot):

Skritter accepts both these stroke orders, so you can choose which standard you want to follow.

5. How to learn the stroke order of Chinese characters

The traditional way of learning stroke order is simply to look up the stroke order for each character you learn.

Most textbooks and other traditional learning materials of course includes this information and will show you the step-by-step process for each character

You can also generate such exercise sheets yourself by using one of the tools presented here:

The reason we have gone through the rules in this article is of course that stroke order is much easier to learn if you rely on these general principles.

Once you’ve been writing characters for a while, you’ll stop thinking too much about stroke order.

Learning stroke order as a beginner

If you’re a beginner, though, wouldn’t it be nice if you could get immediate feedback on your stroke order for every stroke you write, without having to look anything up? Well, that’s exactly what Skritter does!

This is qualitatively different from looking at the correct stroke order while writing.

When learning something, active retrieval leads to much longer-lasting memories than passive recognition, meaning that if you see whatever it is you’re trying to learn, you’re not going to learn as much.

Skritter allows you to write on your own and prompts you only when you make a mistake or forget what the next stroke is supposed to be.

If you look at the animation here, you can see the student writing each stroke, but then forgetting the fourth stroke. Skritter to the rescue!

If you look at the animation here, you can see the student writing each stroke, but then forgetting the fourth stroke. Skritter to the rescue!

Writing on screen vs. writing on paper

Even if Skritter is a great tool for learning stroke order, we still suggest that you write characters on paper now and then. The reason for this is one of validity, or in other words, you need to make sure that the study method you use leads to the results you’re after.

We know that using Skritter to learn characters transfers well to writing on paper because we have done it ourselves. You can read about one example of this here.

Still, writing on a screen and writing on paper are not exactly the same thing, so do bring out pen and paper now and then to verify that you can write that way, too.

If you’re not a beginner and want to make sure that you get the most out of your learning in Skritter, we suggest that you enable raw squigs.

If you look at the animation above of the character 我 being written, you can see that each stroke looks very neat and snaps into place. This is great for reinforcing a good model of what the character is supposed to look like, which is awesome for beginners!

Stroke order beyond the beginner stage

However, if you’re well past that stage of learning and want to make sure that Skritter really prepares you for writing on paper, you should enable raw squigs, which removes the snapping and redrawing of the strokes. Instead of seeing a pretty, computer-rendered font, you’ll see your own handwriting in all its glory.

This is important because it is sometimes possible to cheat using the snapping function. What if you actually intended to write a similar stroke, but Skritter then reveals the correct one?

That means Skritter thinks you know the stroke, but if you would have had no support, you would actually have gotten it wrong. Enabling raw squigs gets rid of this problem! You can read more about the risk of cheating and why raw squigs are great here.

6. More about the strokes used to write Chinese characters

You now know everything you need to know about stroke order in Chinese, but what about the strokes themselves? As a beginner, you don’t really need to care about strokes unless you’re interested in calligraphy, but the more Chinese you know, the more relevant it becomes.

We made this video to teach you everything you need to know about strokes:

7. Chinese character stroke order resources

We have already mentioned several useful resources for learning stroke order in Chines, but there’re are many more resources out there!

Here’s a brief summary of some of them based on this article from Hacking Chinese. Below, we have only included some of the links, so if you want to know more about each and how to use them, please refer to the original article.

About stroke order, why it matters, and things to be aware of

- Is it necessary to learn the stroke order of Chinese characters? (article)

- Chinese Stroke Order Rules (video)

- The Core Chinese Strokes You Need to Know (video)

More about handwriting in general

Is it necessary to learn to write Chinese characters by hand?

Is it necessary to learn to write Chinese characters by hand? - How to improve your Chinese handwriting (article)

- Chinese character variants and fonts for language learners (article)

- Handwriting Chinese characters: The minimum requirements (article)

Looking up stroke order

Arch Chinese (web)

Arch Chinese (web)- YellowBridge (web)

- LINE Dictionary (web)

- 现代汉语通用字笔顺规范 (authoritative (mainland), book, PDF)

- 國語辭典 (authoritative (Taiwan), web, app)

- 中英對照香港學校中文學習基礎字詞 (authoritative, Hongkong, web)

Printable worksheets with stroke order

田字格字帖生成器 (web)

田字格字帖生成器 (web)- 宝宝学习网 (web)

- Chinese Character Worksheets (ArchChinese, web)

- Chinese Practice Worksheet Generator (Purple Culture, web)

Tools and apps for learning stroke order

Other stroke order resources

Wikimedia Commons Stroke Order Project (web)

Wikimedia Commons Stroke Order Project (web) - How to look up Chinese characters you don’t know (article)

- 21 essential dictionaries and corpora for learning Chinese (article)

Stroke order animations for 必 (必-order.gif, 必-torder.gif and 必-jorder.gif) were created by Cangjie6 and licensed under Creative Commons BY 3.0.