![]() I promised Nick I wouldn’t be a grump while writing this post, so let’s kick things off with a tragically funny comic I found on Laowai Comics:

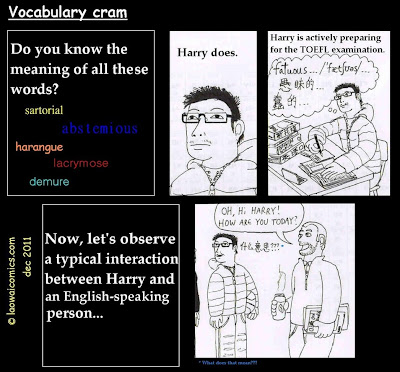

I promised Nick I wouldn’t be a grump while writing this post, so let’s kick things off with a tragically funny comic I found on Laowai Comics:

|

| Who really wants to be like Harry? (image from Laowai Comics) |

If you’ve lived in China or Taiwan you are certainly familiar with the Harry type; a total machine at “learning” vocabulary who couldn’t carry on a decent conversation in the target language to save their life. It’s clear that Harry has a case of list overdose. Never heard of list overdose? Let me give you the textbook definition:

List overdose (or simply LOD) describes the ingesting or constant studying of vocabulary lists in quantities greater than are recommended or generally practiced. LOD may result in very little actual linguistic improvement (emphasis added).

Okay, so I just made up LOD, but if it were real the phenomenon would be an epidemic sweeping digital language learning… and why not, now that we have access to everything from the HSK Lists 1-6 to the 3500 most common characters and beyond? As Confused Laowai (Niel) pointed out in his own research, simply knowing 100 of the most common characters would, in theory, give you access to a 1128-word vocabulary. Therefore, the logic, I think, behind studying massive vocab lists (or frequency lists) seems to be that extended studying of individual words will amount in increasing levels of fluency.

But is that really the case?

As LOD suggests, studying from these lists is generally not going provide any actual linguistic improvement, especially at lower levels of language learning. This is because knowing many words (and creating language) is not just about the sum of individual words, but rather the important mental interconnections that are formed by the words we know. What do these mental interconnections include, you ask?

In 1987, Håkan Rignbom characterized word knowledge using the following six dimensions:

- Accessibility– the ability to access a word from our mential lexicon

- Morphophonology– knowledge of a word’s pronunciation and spelling in various forms

- Syntax– knowledge of a word’s grammatical class and syntactic constraints

- Semantics– knowledge of the meaning(s) of a word

- Collocation– knowledge of multiword combinations and when a word conventionally occurs

- Association– knowledge of the word’s association with other words and notions.

Proficiency then doesn’t come from knowing a bunch of individual words (the basic outcome of LOD), but rather how we mentally link words together. Context, for one, is an incredibly important part of forming these mental links in both comprehension and production. It helps shape mental connections, giving us insights into syntax, semantics, and collocation. Skritter’s upcoming launch of Example Sentences 2.0 will hopefully help a lot in that regard, but nothing beats seeing, hearing, and using words in the wild.

Is there a time and place for these lists, and the studying of them? Of course, but I’ll save that for another post. For now, I simply want to remind you all of the dangers of LOD. Cause let’s face it… who really wants to be like Harry?