![]() Using a textbook, dictionary, flashcards or phrasebook to study Chinese, there no doubt that the modern phonetic transcription of Chinese characters, know as Pīnyīn, is a great aid to learning to speak and understand the Chinese language. Recently I’ve been reading research by Michael E. Everson, a prolific researcher in the area of Chinese as a Foreign Language (CFL), and am fascinated by what some of his research suggests in regard to Pīnyīn (here I am referring to it as phonological code for Chinese) as it relates to word recognition. In a paper titled “Word Recognition among Learners of Chinese as a Foreign Language: Investigating the Relationship between Naming and Knowing,” his research among beginning CFL learners indicates a strong relationship between correctly pronouncing Chinese words and the ability to correctly identify their meanings (Everson 1998).

Using a textbook, dictionary, flashcards or phrasebook to study Chinese, there no doubt that the modern phonetic transcription of Chinese characters, know as Pīnyīn, is a great aid to learning to speak and understand the Chinese language. Recently I’ve been reading research by Michael E. Everson, a prolific researcher in the area of Chinese as a Foreign Language (CFL), and am fascinated by what some of his research suggests in regard to Pīnyīn (here I am referring to it as phonological code for Chinese) as it relates to word recognition. In a paper titled “Word Recognition among Learners of Chinese as a Foreign Language: Investigating the Relationship between Naming and Knowing,” his research among beginning CFL learners indicates a strong relationship between correctly pronouncing Chinese words and the ability to correctly identify their meanings (Everson 1998).

For researchers like Everson, word recognition goes beyond simply knowing how to say a specific character correctly; it also is an important process in overall reading comprehension. Word recognition particularly merits further research among languages like Chinese, whose orthography (a standard system for a particular writing system) represents phonology in a way that is quite different from alphabetic systems. Much of Everson’s paper explains and identifies how Chinese characters are “represented orthographically in imprecise and irregular ways,” or rather, that newly encountered Chinese words are very hard to pronounce correctly if you’ve never seen them before (until reaching a very advanced language level). However, the point of interest for me, and hopefully for you, is the larger question Everson is asking with this paper, namely: to what extent can learners use “ideographic processing” (use simply an image to identify meaning) to compensate for the absence of pronunciation cues (Everson 1998).

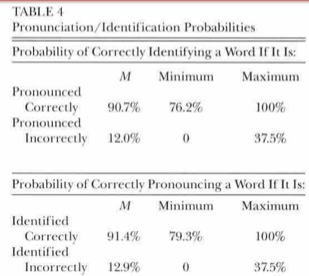

In order to test this hypothesis, 20 beginning CFL learners were asked to pronounce 46 Chinese words that they had previously studied over the course of 180 classroom hours (learning roughly 500 characters), into a computer program specifically designed to display these words. Upon completion, the subjects were then given a sheet of paper and asked to write the English meaning of each of the Chinese words that appeared in the study. So what did the study find? Take a look at the image below:

- That spoken language support (and Pīnyīn) is crucial to helping solidify beginning literacy skills (i.e. spend lots of time speaking, and speak what you are reading).

- That beginning learners should try to focus on more unauthentic, pedagogically based materials like guided readers, or textbooks rather than frequency lists or pages of a dictionary.

- If you are not already at a very advanced level, don’t even think about turning off reading prompts, ’cause you never know when naming a word could be the key to knowing it.

In other news, the Skritter October newsletter just went out–a day late because it took so long to count all the reviews y’all did and generate the statistics! We’ve got some new features in there this month, so check it out.